You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Scraps of Worldbuilding

- Thread starter Andrenne

- Start date

"Why do we raid?"

"We Xuěrén don't have any iron."

"Why do we need iron?"

"To make weapons."

"Why do we need weapons?"

"To raid!"

-Feng Bao explaining to Zou Mingyu their way of life in Ba Feng. Unkown date. Estimated more than a thousand years ago. And now today a funny proverb regarding the cyclical nature of life.

"We Xuěrén don't have any iron."

"Why do we need iron?"

"To make weapons."

"Why do we need weapons?"

"To raid!"

-Feng Bao explaining to Zou Mingyu their way of life in Ba Feng. Unkown date. Estimated more than a thousand years ago. And now today a funny proverb regarding the cyclical nature of life.

Last edited:

Dødsgrop Prison

Est. 1893.

Capacity 999.

Current population 633.

Underground prison. Panopticon. Nine Stories tall. One hundred eleven cells per floor. A Multitude of amphitheaters for general lecture. Singular Central Water Tower. Two Prison Personnel Barracks.

Chief Director: Erik Wollum. 2001-Present

Famous for its chili dogs.

"Welcome to hell!"

Last edited:

MacSalterson

TNPer

- Pronouns

- They/Them

On The Role of Lighthouse Keepers As Executioners in Ajóvulką

The coasts of Ajóvulką are often marked for their inhospitality. Unforgiving sheer cliffs and stoney shores, with rock reefs reaching out into the sea like the spines of some ancient sea-beast. Even in the modern day, more ships than one might expect are claimed by sea, their hands and captains often with little chance of survival in the frigid northern waters. It is no surprise then that lighthouse and pyre keepers have such an important role in Ajóvulkansk history, culture, and even mythology. What might surprise one, however, is that these individuals had roles beyond protecting sailors. Indeed, the historical role of the Balforðyr (the Ajóvulkansk name for pyre and lighthouse keepers) included that of executioners and the priests of Ösafryni, the fell sea god.

The group that would become the modern Ajóvulkans arrived to the islands in the middle of the 10th century, BCE. Upon arriving, they merged with the small extant population on the island, largely overtaking them culturally. However, a few touchstones of the previous culture survived through this merging. Among these was the importance of the sea and the sea god, known Ozaðąąvo. It is claimed that a pact was made with this god, either by those who came before the Ajóvulkans (and upon arriving to the islands, the Ajóvulkans were joined with this pact too) or by the Ajóvulkans themselves when they arrived to the islands. The pact was that Ozaðąąvo, or Ösafryni as he would come to be known, would protect the Ajóvulkans from the sea; they would sail freely with the wind at their backs and the waves in their favor, their pyres and later lighthouses would not be torn asunder by the elements, their fish and whale would be bountiful, and their bays and inlets calm. In exchange, the Ajóvulkans would offer up those who they would execute - pirates, kinslayers and mass murderers, traitors, necromancers and warlocks, and some captured prisoners from raids to the sea god to claim instead of enacting justice with their own hands. The duty was given to the Balforðyr, it is stated, because the Balforðyr saved sailors from being claimed by the sea. Thus, if they save lives from Ösafryni, they should also give lives to him.

And so they did. The Balforðyr became Ösafryni's priests and the executioners of Ajóvulką. They would be respected, if perhaps feared, by most Ajóvulkans for their assigned role. The children they bore would continue their work, or if they bore no child, an apprentice gifted to them by a nearby village or the jarl of the island, such that pyres were rarely left with no one to tend them. If a Balforðyr saw to abandon their duty, they would be offered up to Ösafryni themselves.

These execution-sacrifices were carried out in a small number of different manners across Ajóvulką. The most common by far involved taking those condemned to death at low tide to the water's edge, typically just below the pyre or lighthouse, and shackling or chaining them to the rocks. As the tide came in, the condemned would either drown, freeze to death, or be pummeled to death by the waves. This manner of execution was known as Maargyldi (gull-tribute). In some instances, where the shore was more forgiving, the Balforðyr would carry out the execution in a more personal manner. They would walk the condemned into the water until waist high and would submerge the condemned until they drowned, then cut their throat using a blade made of driftwood or stone from the ocean (called a Rekisag or Rekasek). This manner of execution was known as Drekjagyldi (drowning-tribute). The last common method of execution-sacrifice was to burn the condemned alive on the pyre of the Balforðyr. Though the condemned was not drowned this way, it was stated that Ösafryni was still satisfied, as the condemned were killed by a tool used to save others. This manner of execution was known as alternatively Eldrgyldi, Balgyldi (both meaning fire-tribute), or Heðagyldi (mockery-tribute).

The coasts of Ajóvulką are often marked for their inhospitality. Unforgiving sheer cliffs and stoney shores, with rock reefs reaching out into the sea like the spines of some ancient sea-beast. Even in the modern day, more ships than one might expect are claimed by sea, their hands and captains often with little chance of survival in the frigid northern waters. It is no surprise then that lighthouse and pyre keepers have such an important role in Ajóvulkansk history, culture, and even mythology. What might surprise one, however, is that these individuals had roles beyond protecting sailors. Indeed, the historical role of the Balforðyr (the Ajóvulkansk name for pyre and lighthouse keepers) included that of executioners and the priests of Ösafryni, the fell sea god.

The group that would become the modern Ajóvulkans arrived to the islands in the middle of the 10th century, BCE. Upon arriving, they merged with the small extant population on the island, largely overtaking them culturally. However, a few touchstones of the previous culture survived through this merging. Among these was the importance of the sea and the sea god, known Ozaðąąvo. It is claimed that a pact was made with this god, either by those who came before the Ajóvulkans (and upon arriving to the islands, the Ajóvulkans were joined with this pact too) or by the Ajóvulkans themselves when they arrived to the islands. The pact was that Ozaðąąvo, or Ösafryni as he would come to be known, would protect the Ajóvulkans from the sea; they would sail freely with the wind at their backs and the waves in their favor, their pyres and later lighthouses would not be torn asunder by the elements, their fish and whale would be bountiful, and their bays and inlets calm. In exchange, the Ajóvulkans would offer up those who they would execute - pirates, kinslayers and mass murderers, traitors, necromancers and warlocks, and some captured prisoners from raids to the sea god to claim instead of enacting justice with their own hands. The duty was given to the Balforðyr, it is stated, because the Balforðyr saved sailors from being claimed by the sea. Thus, if they save lives from Ösafryni, they should also give lives to him.

And so they did. The Balforðyr became Ösafryni's priests and the executioners of Ajóvulką. They would be respected, if perhaps feared, by most Ajóvulkans for their assigned role. The children they bore would continue their work, or if they bore no child, an apprentice gifted to them by a nearby village or the jarl of the island, such that pyres were rarely left with no one to tend them. If a Balforðyr saw to abandon their duty, they would be offered up to Ösafryni themselves.

These execution-sacrifices were carried out in a small number of different manners across Ajóvulką. The most common by far involved taking those condemned to death at low tide to the water's edge, typically just below the pyre or lighthouse, and shackling or chaining them to the rocks. As the tide came in, the condemned would either drown, freeze to death, or be pummeled to death by the waves. This manner of execution was known as Maargyldi (gull-tribute). In some instances, where the shore was more forgiving, the Balforðyr would carry out the execution in a more personal manner. They would walk the condemned into the water until waist high and would submerge the condemned until they drowned, then cut their throat using a blade made of driftwood or stone from the ocean (called a Rekisag or Rekasek). This manner of execution was known as Drekjagyldi (drowning-tribute). The last common method of execution-sacrifice was to burn the condemned alive on the pyre of the Balforðyr. Though the condemned was not drowned this way, it was stated that Ösafryni was still satisfied, as the condemned were killed by a tool used to save others. This manner of execution was known as alternatively Eldrgyldi, Balgyldi (both meaning fire-tribute), or Heðagyldi (mockery-tribute).

Predice

TNPer

Shoulder Arms of the Predicean Army of the early 19th-century

Introduction

This post will detail the shoulder arms used by Predicean soldiers from the 1800s to the 1860s, covering the advancements made in the personal arm of the soldier during the first half of the 19th century. This post will detail weapons used by every arm of the Predicean Army, including infantry, cavalry, artillery, as well as others.

A look back

The Mavoian Army, making up the core of what would later become the Predicean Army used the .69 calibre ADR (Arsenale Ducale Rigotti) Modello 1778 flintlock musket and its variants.

Let's go over them briefly, shall we?

The primary shoulder arm of the Mavoian Army was the Model 1778 Infantry Musket. It was by far the most common shoulder arm issued. It was a further development of the Model 1760 musket, and would see heavy service through the Risorgimento. The piece was 60 inches long, with its various carbine variants being generally around 10-20 inches shorter.

It would see later developments, which we will discuss later.

The Model 1778 Light Infantry Carbine was issued to what it says on the tin; Cacciatori a piedi and other light infantry units.

There is also the Model 1778 Musketoon (Moschettone), issued to artillery troops, as well as wagon train guards.

Finally there is the Model 1778 Dragoon Carbine. As the designation suggests, it was used by dragoons.

All of these muskets were flintlock, .69 calibre, and smoothbore. They were all also issued with bayonets. In all, well over 400,000 Model 1778 pattern muskets were made for the Mavoian Army.

As the early years of the Risorgimento dawned, however, it was decided to rearm the Cacciatori a piedi units. The eventual decision? A rifled musket.

Enter the Model 1805 rifle.

Pictured here with its sword, the rifle was a .625 calibre piece. It of course fired the same old round ball, though in its case it was patched.

The rifle was some 45.75in long, making it a rather handy weapon. It was the first rifled musket ever adopted by Mavoian forces, and would see three decades of service in the Cacciatori a piedi, and later Bersaglieri units. These muskets were accurate and generally reliable pieces, which may raise the question: "Why didn't Mavoia arm all of its troops with the Model 1805?"

A very astute question! The answer is twofold: in order to take advantage of the rifling, the ball had to either be a relatively exact .625 calibre ball. Using such balls complicated loading, as a considerable amount of force had to be exerted to push the ball down the barrel. This significantly lengthened the time needed to load the musket compared to a smoothbore musket. The second reason was that rifling was an additional expense, which Mavoia couldn't really deal with if it wanted to arm everyone with rifles.

There was one thing though, that was the eternal enemy of all flintlock arms: moisture.

The way a flintlock functions, necessitates that a small amount of priming powder be used. If this got wet in any way, the musket was useless.

Solutions to this problem had been sought for over a century with little success, but in the 1820s, at last the eternal enemy of the musket was beaten (mostly).

Enter the percussion cap

In 1822, Predicean inventor Matteo Alessandro de Monti came out with the percussion cap, a solution to wet weather making firearms useless.

The percussion cap was, in essence, a copper cap filled with mercury fulminate. When struck by the hammer, the cap would go off, sending a jet down into the barrel, igniting the main charge and discharging the piece. This was revolutionary, and simplified loading considerably. Although the system was initially only used on a couple of pistols, in 1828, the Predicean Army would adopt its first percussion long arm.

This weapon was the Model 1778/28 percussion conversion musket. It was essentially a Model 1778 flintlock musket converted to the percussion system. Nothing else changed. 90,000 Model 1778 Infantry muskets were eventually converted to the percussion system. The conversion was generally not well regarded, but soldiers would have to make do for twelve years.

The Model 1805 too was eventually converted to the percussion system, adopted in 1830. The Model 1805/30 had a shorter service life than the Model 1778/28, as this conversion was generally very poorly regarded and even considered dangerous.

The Model 1837 rifle was brought into service instead, built from the beginning as a percussion musket, though otherwise externally differing little from the Model 1805 that preceded it. It was a well regarded rifle that would see a decade of service.

In 1840 the new Model 1840 Infantry musket was at last introduced, built from the beginning as a percussion system. Not much else changed, but it was generally well liked, but would not see a long service life.

Also in 1840, the new Model 1840 percussion Dragoon carbine was introduced. It was issued to cavalry, specifically dragoons, as might be expected.

In 1842, the Bersaglieri would get their own carbine.

The Model 1842 Bersaglieri Carbine was a rifled musket that had peculiarities compared to the standard muskets of the era, including the conspicuous spike at the end of the stock, meant for melee fighting, as these muskets were issued without bayonet or sword.

As ever, the primary issue with these rifles was rate of fire. Indeed, rate of fire was the eternal enemy of rifles.

This problem would finally be solved in 1846, when Captain Pietro Alonzo presented the Predicean Ordnance Board a revolutionary solution.

Era of the Alonzo ball

The Alonzo ball was revolutionary. The bullet was conical, and hollow at the base with an iron cup placed in the space. When the musket was discharged, the gasses would push the iron cup to expand, expanding the bullet and allowing it to catch the grooves of the rifling. This allowed the Alonzo ball to be small enough to be loaded with relative ease. It was revolutionary, and the Ordnance Board loved it. For the first time in Predicean history, every man would now have a rifle. A .59 calibre Alonzo ball firing rifle.

This rifle would be the Model 1847 Infantry Rifle. A .59 calibre piece, it bears a heavy resemblance to the Model 1840 Musket. It initially came without sights, however an early 1848 revision brought sights to the rifle.

This .59 calibre piece would become an icon of Predice, serving for two decades. The adoption of the Model 1847 rifled musket brought a paradigm shift in Predicean infantry practice as well, blurring the line between light infantry and line infantry. The 1847 Infantry Manual for the first time ordered that every company in a regular line regiment be capable of fighting in extended order.

The Model 1847 Short Rifle was issued to Cacciatori a piedi, and artillery units, as well as Sergeants in line units. Sergeants were expected to supervise fire, not join in, though if needed, they were very much capable of joining in.

The Cavalry were issued the Model 1847 Cavalry Carbine which was a bit shorter than the short rifle.

Finally the Bersaglieri received their own peculiar carbine, the Model 1847 Bersaglieri Carbine. It came with a sword as well.

This sword bayonet, officially known as the Model 1847 Bersaglieri Sword Bayonet, though unofficially almost universally known as the 1847 Bersaglieri Sword, was rarely affixed, as it made loading the rifle dangerous and awkward.

These issues were ironed out in the Model 1850 Bersaglieri Yatagan Sword Bayonet. When affixed, it provided clearance for the hand near the muzzle, allowing the rifle to be loaded safely.

Thus concludes our very brief overview of Predicean muzzleloaders in service from the 1800s to the 1860s.

Introduction

This post will detail the shoulder arms used by Predicean soldiers from the 1800s to the 1860s, covering the advancements made in the personal arm of the soldier during the first half of the 19th century. This post will detail weapons used by every arm of the Predicean Army, including infantry, cavalry, artillery, as well as others.

A look back

The Mavoian Army, making up the core of what would later become the Predicean Army used the .69 calibre ADR (Arsenale Ducale Rigotti) Modello 1778 flintlock musket and its variants.

Let's go over them briefly, shall we?

The primary shoulder arm of the Mavoian Army was the Model 1778 Infantry Musket. It was by far the most common shoulder arm issued. It was a further development of the Model 1760 musket, and would see heavy service through the Risorgimento. The piece was 60 inches long, with its various carbine variants being generally around 10-20 inches shorter.

It would see later developments, which we will discuss later.

The Model 1778 Light Infantry Carbine was issued to what it says on the tin; Cacciatori a piedi and other light infantry units.

There is also the Model 1778 Musketoon (Moschettone), issued to artillery troops, as well as wagon train guards.

Finally there is the Model 1778 Dragoon Carbine. As the designation suggests, it was used by dragoons.

All of these muskets were flintlock, .69 calibre, and smoothbore. They were all also issued with bayonets. In all, well over 400,000 Model 1778 pattern muskets were made for the Mavoian Army.

As the early years of the Risorgimento dawned, however, it was decided to rearm the Cacciatori a piedi units. The eventual decision? A rifled musket.

Enter the Model 1805 rifle.

Pictured here with its sword, the rifle was a .625 calibre piece. It of course fired the same old round ball, though in its case it was patched.

The rifle was some 45.75in long, making it a rather handy weapon. It was the first rifled musket ever adopted by Mavoian forces, and would see three decades of service in the Cacciatori a piedi, and later Bersaglieri units. These muskets were accurate and generally reliable pieces, which may raise the question: "Why didn't Mavoia arm all of its troops with the Model 1805?"

A very astute question! The answer is twofold: in order to take advantage of the rifling, the ball had to either be a relatively exact .625 calibre ball. Using such balls complicated loading, as a considerable amount of force had to be exerted to push the ball down the barrel. This significantly lengthened the time needed to load the musket compared to a smoothbore musket. The second reason was that rifling was an additional expense, which Mavoia couldn't really deal with if it wanted to arm everyone with rifles.

There was one thing though, that was the eternal enemy of all flintlock arms: moisture.

The way a flintlock functions, necessitates that a small amount of priming powder be used. If this got wet in any way, the musket was useless.

Solutions to this problem had been sought for over a century with little success, but in the 1820s, at last the eternal enemy of the musket was beaten (mostly).

Enter the percussion cap

In 1822, Predicean inventor Matteo Alessandro de Monti came out with the percussion cap, a solution to wet weather making firearms useless.

The percussion cap was, in essence, a copper cap filled with mercury fulminate. When struck by the hammer, the cap would go off, sending a jet down into the barrel, igniting the main charge and discharging the piece. This was revolutionary, and simplified loading considerably. Although the system was initially only used on a couple of pistols, in 1828, the Predicean Army would adopt its first percussion long arm.

This weapon was the Model 1778/28 percussion conversion musket. It was essentially a Model 1778 flintlock musket converted to the percussion system. Nothing else changed. 90,000 Model 1778 Infantry muskets were eventually converted to the percussion system. The conversion was generally not well regarded, but soldiers would have to make do for twelve years.

The Model 1805 too was eventually converted to the percussion system, adopted in 1830. The Model 1805/30 had a shorter service life than the Model 1778/28, as this conversion was generally very poorly regarded and even considered dangerous.

The Model 1837 rifle was brought into service instead, built from the beginning as a percussion musket, though otherwise externally differing little from the Model 1805 that preceded it. It was a well regarded rifle that would see a decade of service.

In 1840 the new Model 1840 Infantry musket was at last introduced, built from the beginning as a percussion system. Not much else changed, but it was generally well liked, but would not see a long service life.

Also in 1840, the new Model 1840 percussion Dragoon carbine was introduced. It was issued to cavalry, specifically dragoons, as might be expected.

In 1842, the Bersaglieri would get their own carbine.

The Model 1842 Bersaglieri Carbine was a rifled musket that had peculiarities compared to the standard muskets of the era, including the conspicuous spike at the end of the stock, meant for melee fighting, as these muskets were issued without bayonet or sword.

As ever, the primary issue with these rifles was rate of fire. Indeed, rate of fire was the eternal enemy of rifles.

This problem would finally be solved in 1846, when Captain Pietro Alonzo presented the Predicean Ordnance Board a revolutionary solution.

Era of the Alonzo ball

The Alonzo ball was revolutionary. The bullet was conical, and hollow at the base with an iron cup placed in the space. When the musket was discharged, the gasses would push the iron cup to expand, expanding the bullet and allowing it to catch the grooves of the rifling. This allowed the Alonzo ball to be small enough to be loaded with relative ease. It was revolutionary, and the Ordnance Board loved it. For the first time in Predicean history, every man would now have a rifle. A .59 calibre Alonzo ball firing rifle.

This rifle would be the Model 1847 Infantry Rifle. A .59 calibre piece, it bears a heavy resemblance to the Model 1840 Musket. It initially came without sights, however an early 1848 revision brought sights to the rifle.

This .59 calibre piece would become an icon of Predice, serving for two decades. The adoption of the Model 1847 rifled musket brought a paradigm shift in Predicean infantry practice as well, blurring the line between light infantry and line infantry. The 1847 Infantry Manual for the first time ordered that every company in a regular line regiment be capable of fighting in extended order.

The Model 1847 Short Rifle was issued to Cacciatori a piedi, and artillery units, as well as Sergeants in line units. Sergeants were expected to supervise fire, not join in, though if needed, they were very much capable of joining in.

The Cavalry were issued the Model 1847 Cavalry Carbine which was a bit shorter than the short rifle.

Finally the Bersaglieri received their own peculiar carbine, the Model 1847 Bersaglieri Carbine. It came with a sword as well.

This sword bayonet, officially known as the Model 1847 Bersaglieri Sword Bayonet, though unofficially almost universally known as the 1847 Bersaglieri Sword, was rarely affixed, as it made loading the rifle dangerous and awkward.

These issues were ironed out in the Model 1850 Bersaglieri Yatagan Sword Bayonet. When affixed, it provided clearance for the hand near the muzzle, allowing the rifle to be loaded safely.

Thus concludes our very brief overview of Predicean muzzleloaders in service from the 1800s to the 1860s.

Last edited:

The Pésantini Oilfield

Located within the oil-rich Hariála deserts of central Pozolanni, the Pésantini Oilfield is the largest currently known oilfield within the country. The field shares its name with the Pésantini Depression, both of which are named after geologist Enrico S. Pésantini. Discovered in the 1950s, billions of barrels have been produced here, helping to promote the country's economic development. The oilfield is serviced by the Hariála Rapi-Garr (Quick Transit) Pipeline, which runs eastwards towards the coastal city of Portozar.

Located within the oil-rich Hariála deserts of central Pozolanni, the Pésantini Oilfield is the largest currently known oilfield within the country. The field shares its name with the Pésantini Depression, both of which are named after geologist Enrico S. Pésantini. Discovered in the 1950s, billions of barrels have been produced here, helping to promote the country's economic development. The oilfield is serviced by the Hariála Rapi-Garr (Quick Transit) Pipeline, which runs eastwards towards the coastal city of Portozar.

Tyler the Floridaman

Registered

- TNP Nation

- The Great Florida Empire

Wildlife of Lesta: The Blue Winged Finch

Description

The Blue Wing Finch is a rare finch in the family of Fringillidae. Found exclusively in Lesta the Blue Winged Finch is a bulky headed bird. Its head is orange-brown with a black eye stripe and bib, and a massive bill, which is black in summer but paler in winter. The upper parts are dark brown with white mix in and the underparts are a mix of orange and tan. It is most noted for its blue feathers at the ends of its wings. They are often shy and avoid most other animals and so often like to nest in thick forest near mountains. They eat a variety of nuts, berries, and bugs but have been observed to like the tarwot berry, which is a particularly bitter berry that most animals avoid.

Cultural Significance

The Blue Winged Finch is a very valued animal for their rarity, because of this the finch was important to Lesta's culture. It was often thought of as a messenger of Arzonty the god of peace, because of this it was said that if a Blue Winged Finch landed on you during a time of war or conflict the war or conflict would soon end. As time went on and Lesta's gods were forgotten these birds turned from a sigh of Arzonity to a sigh of power and wealth. These birds were sold for hundreds and sometimes even thousands of Larcs and were a tell tale sigh of wealth. Most rulers of Lesta had at least a pair of these birds. The Lesta royal family has their own sanctuary for them and the Lesta government will often give them to foreign nations as a sigh of trust.

Description

The Blue Wing Finch is a rare finch in the family of Fringillidae. Found exclusively in Lesta the Blue Winged Finch is a bulky headed bird. Its head is orange-brown with a black eye stripe and bib, and a massive bill, which is black in summer but paler in winter. The upper parts are dark brown with white mix in and the underparts are a mix of orange and tan. It is most noted for its blue feathers at the ends of its wings. They are often shy and avoid most other animals and so often like to nest in thick forest near mountains. They eat a variety of nuts, berries, and bugs but have been observed to like the tarwot berry, which is a particularly bitter berry that most animals avoid.

Cultural Significance

The Blue Winged Finch is a very valued animal for their rarity, because of this the finch was important to Lesta's culture. It was often thought of as a messenger of Arzonty the god of peace, because of this it was said that if a Blue Winged Finch landed on you during a time of war or conflict the war or conflict would soon end. As time went on and Lesta's gods were forgotten these birds turned from a sigh of Arzonity to a sigh of power and wealth. These birds were sold for hundreds and sometimes even thousands of Larcs and were a tell tale sigh of wealth. Most rulers of Lesta had at least a pair of these birds. The Lesta royal family has their own sanctuary for them and the Lesta government will often give them to foreign nations as a sigh of trust.

Last edited:

Iraelia

TNPer

The Callisean Far-Right in 2022

Callisean Far-Right Activist and founder of the Patriot Caucus of the Nationalist League, Francis Calvet

The history of the Far-Right in Callise, and it's current position, is heavily influenced by the experience of Callise following the collapse of the National Republic of LeBlanc.

Callisean Far-Right Activist and founder of the Patriot Caucus of the Nationalist League, Francis Calvet

In the years immediately following the collapse of LeBlanc's Republic, the far-right of Callise was largely non-existent. With several members of the National Republic having been tried for crimes against humanity, the primary leaders of this movement were imprisoned, executed, or barred from holding public office. This was a severe impediment to the continued operation of the Callisean Far-Right. However, even in this time, the far-right congregated in the fringes of the Nationalist League. One of the earliest far-right groupings in the Third Republic era Nationalist League was the Patriotic Republican League. Although they were isolated from real power for decades by a Nationalist League which was trying to improve their image in an era where their past in the LeBlanc Consulate was a severe blemish on their record in the eyes of voters.

The growth of the Callisean Far-Right began in earnest in 1986, after the failure of the Nationalist League Courtial Directorate collapsed. At the 1986 party convention, a more right wing faction of the party took control of leadership. While they were not in earnest aligned with the radical nationalist politics of the modern Far-Right, their ranks did include some former members of the now defunct Patriotic Republican League, It was this leadership slate which would run the party until 2005 and influenced their politics in a pro-tariffs, anti-immigration direction while not openly advocating for the political repression, authoritarianism, and reactionary paternalistic politics of the LeBlanc Directorate.

In 2005, the Callisean Far-Right encountered another obstacle in the form of the success of the Barrault Directorate at winning a second term. The nigh-hegemonic power of the Social Democratic led electoral coalition drove the party to seek an alliance with their traditional opponents in the Liberal Party, as well as reconciling with the Progressive Conservatives (a more moderate party which had split from the Nationalist League in the 1920s and who continued to remain separate on the grounds that they opposed the LeBlanc Consulate) and their social base in moneyed interests in the North. This alliance forced the ruling right wing faction from power in favor of a moderately conservative neoliberal bloc.

When the Nationalist League took power in 2015 as a junior partner to the Liberals, trouble started almost immediately. First of all, the Directorate relied on the support of a group of senators which styled themselves as the "National Sovereigntist Caucus," led by Raphael Aubert. While independent, they had previously been members of the Nationalist League aligned to their former right-wing leadership. While most of the members of the political bloc remained in the party, Aubert and some more libertarian elements of the party split off to caucus independent from the Nationalist League. Second, parallel to this National Sovereigntist bloc in the Senate, there was a growing political movement which took its historical cues from the Patriotic Republican League. This undercurrent saw immigration and "demographic change" as an existential threat to Callise, viewed the insurgent Left Party as an internationalist plot to undermine Callise, and promoted a brand of Patriotic Republicanism which idolized the LeBlanc Consulate. For a long time this movement, which primarily lived online, was disorganized and loosely guided by a series of hot button issues. This changed after the 2021 election, which broke the Dupont Directorate's grasp on power and once more forced the Nationalist League into opposition.

Now in opposition once again, the Nationalist League sought to distance itself from the failed project of the Callisean Liberal Party. It invited the National Sovereigntist Caucus back into its ranks and took a decidedly rightward turn. This culminated at the 2022 convention, with the founding of a new internal caucus. A majority of the National Sovereigntist Caucus (notably excluding Aubert), and a young activist corps radicalized by online far-right communities, founded the Patriot Caucus. Modeled on the Patriotic Republican League, this group sought to transform the party from a centre-right to right wing party, into a Blancist party of political reaction. While not a majority, they have formed a plurality of delegates to the 2022 convention, as well as on the executive board of the party. Most notably, they are led by Francis Calvet, a young radical who formerly served as the Chairman of the Youth Nationalists from 2008-2010. Under his leadership, the party has actively begun to propagandize about preserving Callise's "national character" and to restore patriotism in the Callisean Republic.

It is unclear what the future holds, both for Callise and the right-wing extremists within it. But with the Callisean Left ascendant, talk of a Bennet Directorate, and the proposition of radically democratic constitutional reform, the reaction of the right is both uncertain and anxiously anticipated.

Last edited:

A Curious Case: Section 5.1.1 of the Supreme Law of Goyanes

Adamsson Landkreis Courthouse, where the events of January 25, 2007 unfolded. (Pictured 2015)

The Supreme Law, an over 300-year-old document, is the constitution of Goyanes. It is a document that has been one of the great constants of Goyanean society through history, standing along its ancient monarchical institutions and the Courantist faith. While sections have been amended, added, or removed over the years, one has remained intact, somehow.

Adamsson Landkreis Courthouse, where the events of January 25, 2007 unfolded. (Pictured 2015)

The section is 5.1.1. It is a subtext to the first law of the Judiciary section of the Supreme Law. It reads: “A jester may be provided to any court in the realm pursuant that there are no cases of importance to hear.” While this may have been an important concern in the early 18th century, one might wonder if this has been used in modern times.

The date was January 25, 2007. An average winter day in the rural Adamsson Landkreis in Nordgotmark in southern Goyanes. The Landkreis’ magistrate court, located in the eponymous town of Adamsson, had seen little cases that day. The Landkreis was a sleepy place, and by noon, the court had finished the docket. Instead of simply calling it a day, the magistrate’s court’s senior judge, Hans Eidelstein, decided they were going to execute section 5.1.1 of the Supreme Law. By 1 PM the call had been made to the Chancellery of Justice, which begrudgingly accepted (due to their constitutional obligation).

The Vice Chancellor of Justice at the time, Maria Neysveg, upon learning of the call, immediately told her aides “there is no requirement that it be a quality jester in the Supreme Law.” This led to a junior official searching the Igenass (the closest major city to Adamsson) newspaper classifieds for the comedian with the cheapest hourly rate (thus the one of poorest quality, supposedly).

By 4 PM the jester had arrived in Adamsson by local train and presented at the courthouse. Joakim Hammar, a 23-year-old former college student who flunked out of the Nærøy Maritime University, was standing at the front of a courtroom turned makeshift auditorium, before the court’s judges, clerks, aides, and staff, even the janitors. What followed was—according to the South Nordgotmark Herald— “the worst attempt at ‘comedy’ possibly ever seen in Gothis.” Hammar was reported to have spent an hour and a half cracking unfunny jokes, dishing potshots at Igenass city government officials (of which the Adamsson court staff knew virtually none of), and making fun of the appearance of court employees.

The experience was so awful for the court staff and judges that Judge Eidelstein reportedly got fed up and pulled two thousand-Dram bills from his wallet and told him to “take this, get a cab, and never come back here again.” Hammar received a government check two weeks later for ∆360 (~40 IBU (2007)) which compensated him for his hourly wage and the train fares.

The next day, news began to reach the press about the incident, and the Adamsson Magistrate’s Court released an official statement on the affair, stating “Our court cannot recommend under the current circumstances that any court in Goyanes exercise their right under Sec. 5.1.1 of the Supreme Law.” Since then, due to fear of similar incidents, 5.1.1 has not been known to have been initiated by any of Goyanes’ courts.

Last edited:

The true story of Goyanes’ first Astronaut: Thor

In 1967, in preparation for Goyanes’ future manned space launches, the GLR, Goyanes’ space agency (then an joint program of the Chancellery of Defense and the Imperial Academies of Science in its infant years), needed to test the functioning of the life support systems aboard the first generation of space capsule in use at the time. Furthermore, there was a desire to prove that an intelligent mammal could perform tasks in space. The GLR leadership felt a chimpanzee would be the perfect test subject and sent out a request to acquire chimps for use in the project.

25 chimpanzees were bought from an Ascalonian rare animal dealer in 1968 and shipped to Goyanes. These chimps were subject to a screening process where cooperative ones were chosen to be “astronauts,” and the non-selected would be donated to zoos across Goyanes as a goodwill gesture. Of these 25, 6 were selected for the program and began training. A young male chimp named “Thor” by the GLR testing engineers was immediately singled out as the most intelligent of the bunch and was selected to be the first that would go to space.

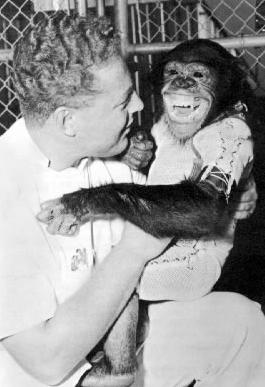

Thor with one of his handlers during training.

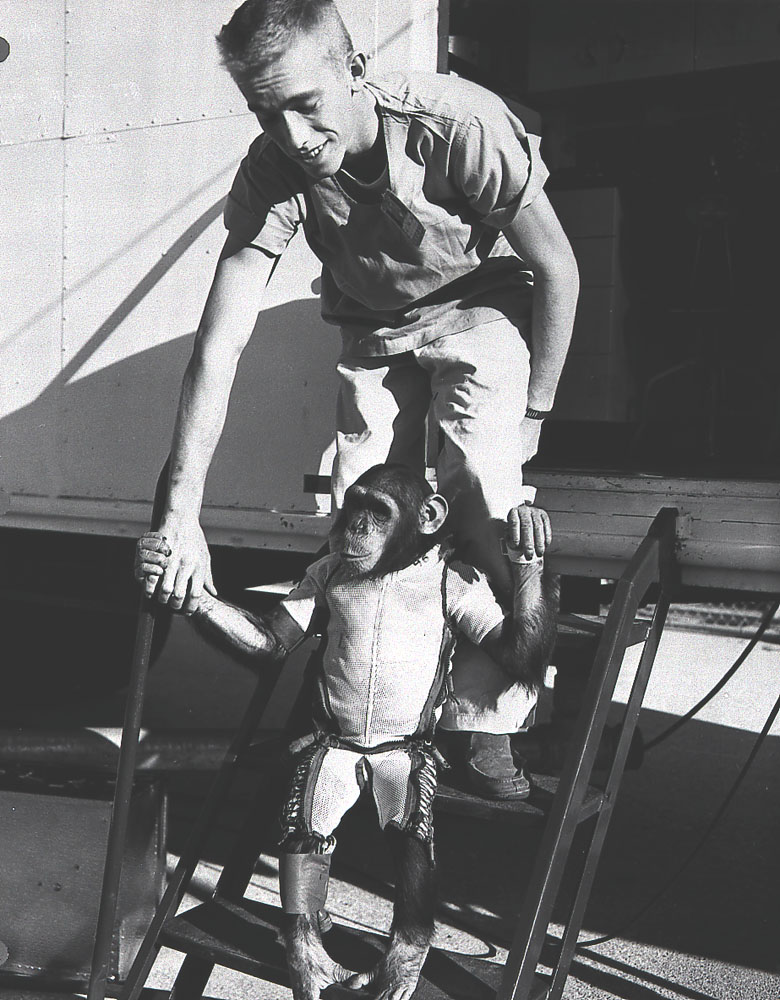

Thor enjoyed wearing his spacesuit even when not doing training operations.

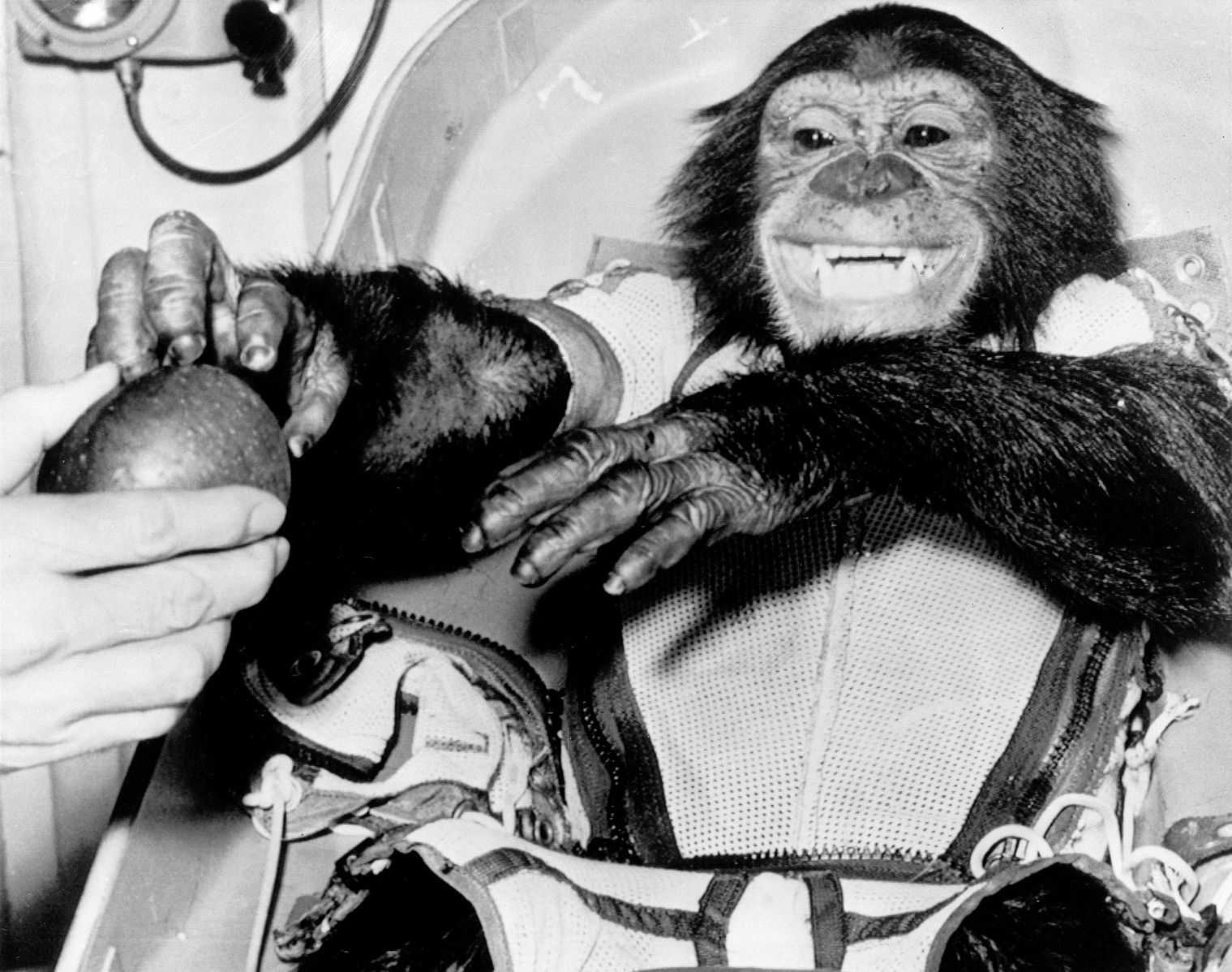

Thor receives his apple during the before launch preparations.

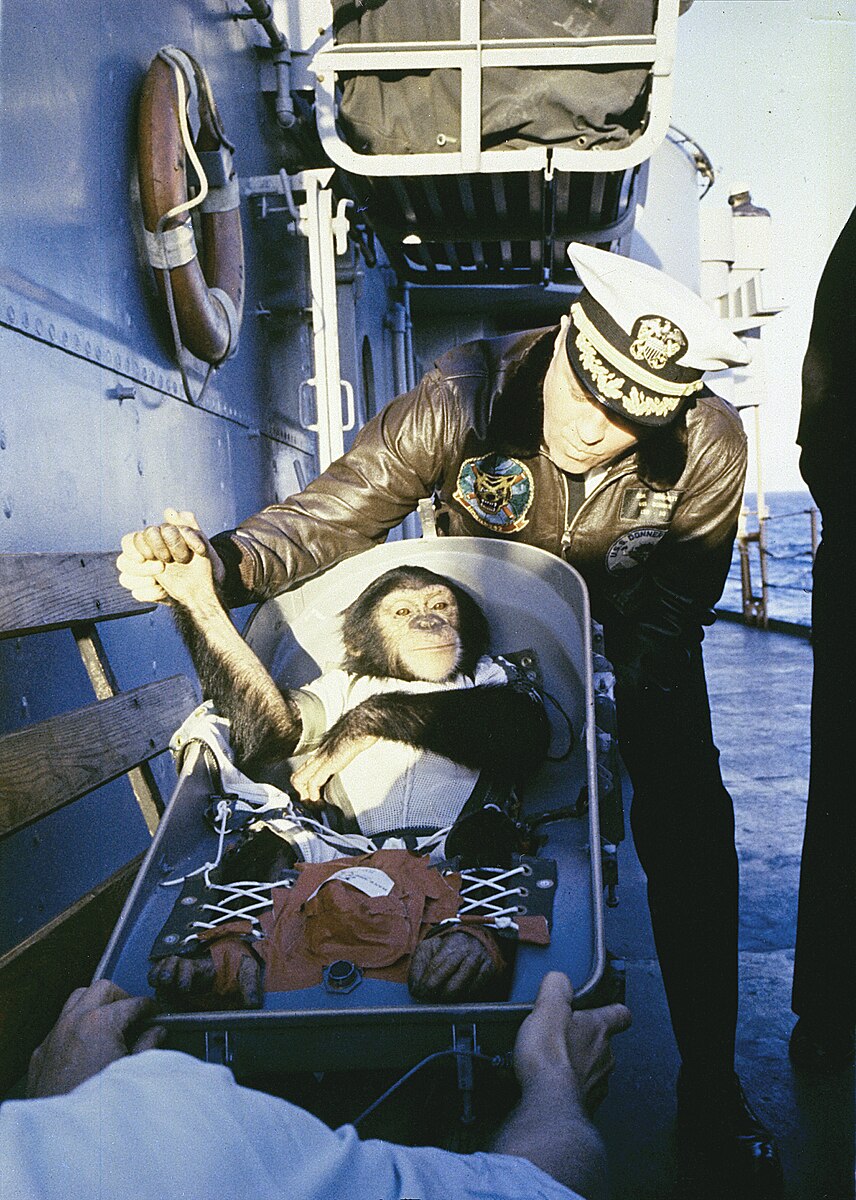

Thor had completed all of his tasks successfully according to the mission data recorders, and as a result of his good performance, the captain of the HMS Oslo the Great, Rikard Eidervik, made him an official member of the carrier’s fighter wing, dubbing him Lieutenant Thor, and was given a set of Goyanean naval wings. Furthermore, the ship’s chef had a feast of banana smoothies, apples, and a variety of other chimp-favorites ready for him in the officer’s mess after his evaluation by the GLR staff aboard the ship.

(Left) Thor is extracted from the capsule after recovery. (Right) Thor is greeted by the ship's captain, Commodore Eidervik, and given the honorary rank of Lieutenant.

The newly commissioned Lieutenant Thor was soon transferred after his mission to the Imperial Zoological Gardens in Gojannesstad, where he happily lived the rest of his life until his death in 1993. While at the zoo, Lt. Thor started a chimp-family with Lana, a female chimp at the zoo, having numerous offspring. Descendants of Thor and Lana are still alive, his grandchildren still being fan-favorites at the Imperial Zoo, where a large exhibit chronicling his experience was constructed shortly after his death in 1993.

Lieutenant Thor was buried with full military honors at the Imperial Astronauts Cemetery at the GLR headquarters in Naderfjord, Nyhett. His grave is a pilgrimage for any space interested Goyanean, and people of all ages continue to leave flowers and pay tribute at his grave.

Christmas Traditions of Kaliva

The celebration of Christmas was first brought to Kaliva by the Prydanians, alongside Blárkristurjól/Blue Christmas. Associated with this holiday is the mythical figure known as Shishira Kóngor, or Winter King, an elderly winter spirit who is said to provide blessings and fortunes to those who have accumulate positive karma throughout the year. Those who have accumulated negative karma throughout the year will be cursed with misfortune. Shishira Kóngor's companion is known as Jultacha, or Jule Goat, a magical goat who travels alongside the Winter King during Christmas and assists him in delivering good spirits and gifts during the Christmas season. Jultacha often appears during Christmas festivities in the form of a festive ornament hung on Christmas trees; superstitions state that the presence of a miniature Jultacha in the house will entice good spirits to visit and provide blessings. Often times, cities will erect large sculptures of Jultacha during the holiday season.

Artist's rendition of Shishira Kóngor and Jultacha delivering

presents and fortune during the Christmas season.

The celebration of Christmas was first brought to Kaliva by the Prydanians, alongside Blárkristurjól/Blue Christmas. Associated with this holiday is the mythical figure known as Shishira Kóngor, or Winter King, an elderly winter spirit who is said to provide blessings and fortunes to those who have accumulate positive karma throughout the year. Those who have accumulated negative karma throughout the year will be cursed with misfortune. Shishira Kóngor's companion is known as Jultacha, or Jule Goat, a magical goat who travels alongside the Winter King during Christmas and assists him in delivering good spirits and gifts during the Christmas season. Jultacha often appears during Christmas festivities in the form of a festive ornament hung on Christmas trees; superstitions state that the presence of a miniature Jultacha in the house will entice good spirits to visit and provide blessings. Often times, cities will erect large sculptures of Jultacha during the holiday season.

Artist's rendition of Shishira Kóngor and Jultacha delivering

presents and fortune during the Christmas season.

Iraelia

TNPer

A Brief Outline of Pre-Revolutionary Callisean History

- 4700 BCE ~ The oldest date of a ruin built by the Spherical Urn Culture, the first documented society to inhabit Callise

- 1000-500 BCE ~ The Prydeinig peoples, ancestors of modern-day residents of Gwladacan, settle Callise and transform into the Callic people by intermixing with the local population. Callic referring to the Prydeinig word for chalice, a reference to a mythical Prydeinig king who supposedly chose to settle in Callise when he supposedly saw a vision of a chalice overflowing with wealth in the West.

- 300 BCE-100 CE ~ The height of Callic civilization, with disparate clans organized around small towns and hillforts surrounded by farms. A druidic religious caste largely controls society, but shares responsibility with an elective nobility composed of able warriors.

- 200 CE ~ An influx of migrants from Aydin into modern day Villende begins the process of the formation of the modern day Villendean people.

- 331 CE ~ According to legend and church documentation, Saint Baldwin landed in what would become modern day Villende. Upon arrival, after witnessing the guards of the city harassing a store owner for money, he was moved by compassion and flung himself over the man. He was imprisoned for three years, but was able to secure an audience with the king when he had heard Baldwin was a healer. The king, whose eldest was dying of leprosy, asked Baldwin to help him. Baldwin told him that the only way to heal him was to have faith in the Messiah, and convinced the king to let him baptize the boy. When the heir emerged from the bath, all signs of leprosy had been cleansed from him. As a result, the people of Villende would be the first Calliseans to convert to Messianism.

- 400-500 CE ~ Ceretic peoples, many of them Messianist, travel across the Phoenix Strait and invade Callise. The resulting mix of Ceretic and Callic culture would eventually lead to the formation of modern day Calliseans.

- 500-700 CE ~ The Septarchy is established, seven petty kingdoms presiding over Callise with Ceretic nobility

- 548 CE ~ The Kingdom of Oèstrègne (modern day Villende) attains ecclesiastical importance as the Archbishop of Sainte-Beaudoin (where Saint Baldwin first landed) is made one of the five members of the Pentarchy (alongside the Via, Ceretis, Maloria, and Arrandal).

- 700-900 CE ~ The Septarchy is further consolidated into three states: Oèstrègne, Sudrègne, and Nòrdrègne.

- 976 CE ~ The Kingdoms of Sudrègne and Nòrdrègne merge via marriage of the only direct heir of Sudrègne, Princess Amabilla, and the first born male heir of Nòrdrègne, Prince Hugo of House Gardet, forming Calaisrègne, more commonly called the Kingdom of Callise.

- 1011 CE ~ King Alfons of Oèstrègne, uncle of Princess Amabilla, passes with no male heirs and the crown enters a disputed succession. The firstborn son of Amabilla and Hugo (and Grandnephew of Alfons), Henri, has the best claim. However, the church rules in favor of giving it to his Great Grandnephew Gregori.

- 1012-1031 CE ~ The Nigh Twenty Years War breaks out, between newly crowned King Gregori, and the Kingdom of Callise. While Callise is initially successful, taking Sainte-Beaudoin in 1015 CE, the city is abandoned with no one in it. From 1015 CE to 1020 CE, Gregori wages a guerilla campaign against the occupying Callisean forces. In 1022 CE, many of the knights and men-at-arms largely abandon the Kings army in order to return to their homes. With their reduced forces, Gregori has the confidence to launch a counter attack and retake Sainte-Beaudoin, which he does in 1023 CE. From 1023 CE to 1027 CE, a de facto cease fire occurs. By now, Henri has ascended to the throne. In 1027 CE, after rebuilding the army, he sends an ultimatum to Gregori demanding he pay tribute to Callise. Gregori refuses, and Henri marches on Oèstrègne. However, rather than march straight for the city, he sets the countryside and forests on fire and proceeds to systematically surround and trap Gregori in Sainte-Beaudoin. By 1030 CE, all of Villende was controlled by Henri and he marched on Sainte-Beaudoin. In 1031 CE, he publicly beheaded Gregori and forced Gregori's descendants to sign a treaty acknowledging his right to rule Villende in exchange for continued residence at Sainte-Beaudoin under the care of his men (essentially making them captives for the rest of their lives).

- 1150s CE ~ Callise participates in the crusades, but rolls back its involvement after Laurens de Maynon is convicted for war crimes and goes rogue.

- 1288 CE ~ The Gardetian Dynasty comes to an end when the King dies without any direct or indirect heirs after a plague had swept Callise, and very little precedent for how to handle the situation.

- 1288-1298 CE ~ The Ten Years War breaks out, with several factions fighting for control of the throne.

- 1299 CE ~ The Reimota is held in Fontaine, where House Mignard are named the monarchs and clear rules for succession are hammered out.

- 1300 CE ~ The Gregorià, a faction of Villendean nobles, assert that the Reimota invalidated the prior treaty recognizing the rule of the Gardetians in Callise.

- 1301-1316 CE ~ The First Villendean Revolt occurs, with a descendent of Gregori taking the throne and aided by local nobility. The war is a slow slog, with the war remaining a stalemate until 1314 CE, when the first Trebuchets were introduced. The lands of Villende were heavily fortified, and the use of these siege weapons successfully broke the stalemate. The traitors were executed in 1316 CE.

- 1357-1361 CE ~ The Second Villendean Revolt occurs, when provincial taxes are placed on Villende to finance the reconstruction of the Royal Army.

- 1370-1520 CE ~ The One Hundred Fifty Years Peace, a period where Callise experienced relative economic prosperity to other periods in its history. Callise became a regional power and one of the foremost countries on Eras by building economic and commercial connections throughout Craviter and Collandris. Callise also underwent a renaissance during this period.

- 1565 CE ~ Rodolphe Renou, having studied in Prydania and offered a professorship at the University of Fontaine's theological department in 1561, publishes his life's major work: Les Preceptes de la Veraia Fe Messianiste (The Precepts of True Messianist Faith). It quickly became the most widely circulated text in Callise and attracted the attention and ire of the Courantist Church. In 1569 CE, he was summoned to Sainte-Beaudoin to answer the charge of heresy. Renou, having seen the way the Laurenists had been received by the church, refused the summons. He spent the next ten years of his life moving between several towns and shelters around the north of Callise. He was ultimately captured in 1579 CE and held until 1581 CE before he was tried and executed for heresy in Sainte-Beaudoin.

- 1582 CE ~ Revenists representing parishes and Revenist nobility met in secret in Millau to discuss the future of the movement. They authored the Millau Confession, one of the chief documents of the Revenist faith. While they were able to agree on that point, they disagreed on the implications and meanings of his teaching. The Redemptors, the majority represented at the meeting, believed that the Kingdom of Callise can be brought in line with Messianist teachings. They were opposed by the Puristes, who believed the entirety of Callisean society had been corrupted by sin and proximity to the Via. The proceedings of the meeting were halted beyond that point, although the Millau Confession remained accepted by both groups. One of the most important points of the confession was that it declared total separation between the Via and the Revenists.

- 1583-1587 CE ~ The Iconoclasm occurs. Following a famine in Northern Callise, the Puristes spurred the peasantry into an open revolt against the nobility. They moved from town to town destroying churches, executing the nobility, and empowering the peasantry. During this period, roughly 75% of all Cathedrals in Northern Callise were burned to the ground. The main brunt of the Iconoclasm was defeated by 1585 CE, but guerilla insurrections continued until 1587 CE.

- 1587-1597 CE ~ The Redemptors, still supported by certain Callisean nobility, are forced to operate in illegality. Many parishes were maintained, which the royal family largely ignored because they wished to avoid more violence following the Iconoclasm

- 1597 CE ~ The nobility of the North form the Liga del Nòrd, a defensive alliance announcing their faith to the nation. The statement of faith it professed would become essential for Revenist faith.

- 1597-1598 CE ~ The Lesser War of Reformation takes place and is quickly fought to a standstill. The Mignardian Dynasty agrees to allow Revenists to practice their faith, but only in regions where the ruler is Revenist.

- 1611 CE ~ Over 10 years after the War of the Northern League, the King of Callise dies with no direct heirs. The heir with the best claim, Phillip of House Lavigne, is a Revenist. The church refuses to crown Phillip and war ensues

- 1612-1624 CE ~ The Greater War of Reformation takes place. Phillip of House Lavigne wins and captures Fontaine in 1618 CE. Most fighting is over by 1619 CE, but Villende, outraged by what they viewed as a heretic sitting on the throne, declared independence once more. They would be forced to surrender in 1624 CE.

- 1624-1701 CE ~ The Lavignian Dynasty rules Callise and had significant influence despite their short reign. They formalized the Revenist and newly established state Church of Callise and established religious autonomy for Sainte-Beaudoin. They also compiled the Livre de Revenou (The Book of Renewal), comprising a variety of historical confessions written by Renou and other Revenist writers. It would serve as the statement par excellence of Orthodox Revenism.

- 1701-1720 CE ~ The throne of Callise is inherited by the Severyns, who begin the process of absolutism in Callise. Despite rabid unpopularity, they liquidated and consolidated much of the nobility, built a national army, and constructed other institutions loyal to the crown alone. When the crown was to pass to the next Severyn, the Callisean nobility waged a War of Succession from 1720-1723 which they lost.

- 1723-1797 CE ~ The Heidenian Dynasty, a cadet branch of the Severyns with ties in Callise, rule Callise. They are Orthodox, but continue to operate as leaders of the Church of Callise. They would be executed in the Callisean Revolution.

Last edited:

Dunkler Wald (Dark forest) LLC

Motto: Responsum ad Quaestionem / Answer to the Question

CEO: Diederich Manstein

Total Staff: 2800

Founders: Dirk Steinbauer, Klaus Daschner, Tomasso Scamacca

Founded: 2013

Headquarters: Anderbergen

Areas Served: Worldwide

Products: Law enforcement training, logistics, close quarter training, and security services

Services: Security management, full-service risk management consulting

Tomasso Scamacca - Born 1965. Served 1983 - 1993. Distinguished himself in 1988 during the five day conflict in the Oclusian Gap. Immigrated to Alemriche in 2003. Moved to Lichten. Started a security firm, “Technical Solutions”, which began training local police and self-defense schools in 2004. He has been responsible for security training for local Alemriche Politicians. During this time, met with AVK agent Klaus Daschner.

Dirk Steinbauer - Born 1987. Born into a wealthy banking family. Graduated Royal Meklenberg Mason Institute in 2010 with B.S. in Economics and Business. Met with Tomasso and Klaus after his father failed to invest in the Security Firm idea. He claims to not have joined out of spite, but the evidence is there.

Klaus Daschner - Born 1982. Born to a middle-class family from Mekleberg. Joined the police academy at the age of seventeen in 1993. After eight years of police work, applied for the AVK. Served in the AVK until 2009 when personal disagreements with state policy disillusioned him. He met Tomasso Scamacca in 2010 during contracted training exercises and assessments. Began work with Scamacca the same year as an instructor in Technical Solutions.

Last edited:

MacSalterson

TNPer

- Pronouns

- They/Them

Homelessness and Transiency in the Stan Yera

Homelessness and housing insecurity are rare in the Stan Yera. The specific number is difficult to measure, for a variety of reasons, but it’s estimated that of the nation’s population of nearly 43 million, around 55,000 to 70,000 individuals experience chronic homelessness, while a further estimated 160,000 to 190,000 individuals are transient workers, truly nomadic, or otherwise not tied to a permanent address. These figures do include some Ânk’aynâ - around 1,700 to 2,100 Ânk’aynâ are known to be homeless, and a further 30,000 to 35,000 do not have a permanent address, out of a total known population of 986,110 and an unknown number of Ânk’aynâ who live independently of Yeran society.

After the Yeran Civil War’s end in 1994, a vast number of people were left homeless, mostly due to internal displacement. As it came into power, Sfan’s regime found their first priority to be ensuring shelter to all residents of the Stan Yera. This eventually led to the introduction of Resolution #ŁIB’96.0209-1 Iśâda śe Âlên Yećakyaľ-ił ć’ Ruśkyan-ił (Mercanti: A Law Protecting Homeless and Transient Peoples), or IÂYR for short. The primary effect of this law was to provide a system for housing homeless individuals - either through the establishment of Yerâƛal B’aćala (Government Housing) and D'amyaƛan B'aćala (Military Housing) or the subsidization of rents in Yeryâƛan B'aćala (Union Housing) or Yerb'ayaƛa B'aćala (Laborer’s Housing, or what might be considered normal tenancy elsewhere). Public works were begun to construct large numbers of new apartment blocks in cities across the Stan Yera as well as refitting and renovating pre-war apartments and tenements where possible. As a result, by 2005 homelessness due to the civil war had dropped dramatically. Another effect of the law was the prohibition and abolition of so-called ‘Hostile Architecture’, or features designed to restrict physical behaviors of those in public spaces. This portion of the law is rumored to have been directly influenced by Sfan’s past during the earlier years of the civil war as a vagrant, before he took up arms and eventually took his current place as Federal Premier of the Stan Yera.

The law similarly protected transient and nomadic populations - either migrant workers who move throughout the country without a fixed address, travelers (including backpackers, hikers, and tourists), or traditionally nomadic and pastoralist groups. It guaranteed a set amount of housing put aside for migrant workers in each urban area, accessible by contacting the municipal government and going through a certification process upon arrival in the town or city where the migrant is seeking work. It also guaranteed to nomads and travelers the ability to own a mailing address, typically a P.O. box in the city of their choosing, where they can receive mail or mark as their place of address. The law also guaranteed the right to free movement within the country to all residents of the Stan Yera.

Resolution IÂYR did not come without its consequences, however. While the law did technically guarantee the right to free movement, during the early stages of its implementation many homeless people were bussed to cities across the country where housing was more readily available, often separating them from support networks and contacts and dumping them in an unfamiliar city that they likely had never even visited. Many individuals often cut and run as soon as they were able, abandoning their assigned housing and attempting to hitchhike back to their cities and towns of origin. This caused numerous conflicts with the military and police, whose attempts to enforce the law resulted in unexpectedly widespread brutality towards homeless individuals. This resulted in nationwide protests and riots, one of the few successful instances of such in the modern Stan Yera. A suit brought before the Federal Procedural Court in August 1999 found such actions as taken by the police and military, as well as the administrators who authorized the forcible transfers, to be unlawful, and recommended and amendment to the resolution banning the forced transfer of homeless people to other cities and towns. Said amendment was passed in October 1999, ending the protests and saving the Stan Yera from potentially disastrous internal unrest. Of course, this in turn had the effect of noticeably lengthening waiting lists for housing, and many were left homeless for far longer than they would've been otherwise. However, it’s rumored that to this day some amount of coerced bussing of homeless people to other cities occurs, despite its ban. The Resolution also has not fully eliminated homelessness in the Stan Yera. Many individuals, often the addicted and mentally ill, are prone to losing their housing or being unable to gain it in the first place despite the government’s efforts to ensure their right to shelter. This number is slowly decreasing, as chronic addiction rates have steadily declined since 2011 and the regime has improved access to mental health resources.

Last edited:

The Kalivese Judicial System operates primarily off of a mixture of both common and civil law. In Kaliva, there are four main levels of courts within the judicial system: Minor Courts, Superior Courts, Appellate Courts, and the Supreme Court of Kaliva. Judicial seats for the Superior Courts, High Courts, and Supreme Courts are elected, although one must be a certified member of the bar in order to seek election to a judicial seat.

As well, there are other special, non-elected courts such as the Labor Relations and Workers' Compensation Court, Insurance Appeals Board, Personnel Board, Business and Commerce Court, Tax Appeals Court, Office of Administrative Law, National Bar Court, and the Armed Services Court that serve to handle legal cases for specific circumstances.

AG-82: The Right Choice

AG-82A Early Model

AG-82A Early Model

The KKT AG-82 is the current service rifle of the Imperial Armed Forces of Goyanes. Designed and manufactured by K.K. Torgesson, the gun is a shoulder-fired, gas-operated assault rifle that fires 5.56x45mm PGU ammunition. The gun replaced the KKT AG-51, a battle rifle made out of G-2 battle rifles of the Fascist War by both Scalvia and Goyanes.

In the early 1960s the Chancellery of Defense felt that the AG-51 was nearing the end of its service life, and ordered the development of a new rifle design. Wanting to keep servicing the large defense contract for standard issue rifles, K.K. Torgesson went to work designing a new rifle. The design went through several prototype iterations, where designers sought to incorporate various design features from other assault rifles in order to manufacture a reliable and effective design.

In 1964, the prototype AG-X12 model was presented to the Chancellery by KKT for testing. The model was approved by the testing commissions, and production commenced on the newly designated AG-82 assault rifle. Some early model AG-82s were distributed to special forces units in 1965. The rifle began to be issued to standard units in 1966, and by 1975, the rifle was in service across the vast majority of Goyanean fighting units.

The basic design features a long-stroke gas piston, folding stock, adjustable gas flow, and integrated ironsights. Furthermore an underbarrel grenade launcher can be used as well. The design has undergone various improvements both in usability and reliability since its introduction and can be summarized into several variants.

AG-82A - The original production model.

AG-82B/B2 - In 1989, following the Gotmark War, lessons learned were integrated into the AG-82, including a top rail for mounting sights, as well as reliability improvements inside the gun. In the mid-90s, B variants began to be produced with a full rail mount system, known as the B2 variant.

AG-82D - In 2000, new directives from the Chancellery of Defense caused KKT to create the AG-82D variant. The D models feature a new rail system, a folding and telescoping stock, and some more durable, yet lighter weight internal components. The vast majority of AG-82s in service in Goyanes are of the B or D variety, mostly the latter.

AG-82U1/2/3 - Foreign sales version of the AG-82B/B2 and -82D, respectively, modified for individual customer needs.

KKT Typ 82 - Domestic consumer sales variant. Does not feature an automatic firing mode and has other modifications for civilian use.

AG-82K - Carbine variant of the AG-82 with full mounting rails and a shortened barrel.

Photos:

AG-82B Variant (left) and a more modern AG-82D (right)

AG-82B Variant (left) and a more modern AG-82D (right)

Last edited:

Longboard

Registered

- Pronouns

- He/Him

Hexastalian Spruce Tea

Spruce tea is a common drink in Hexastalia. Brewed with the spruce needles from the inland regions, you’d be hard pressed to find a Hexastalian who has never at least tried the drink. It’s commonly served hot or room temperature and without sweeteners, though other herbs are usually included in the tea bag for flavor. Some of these herbs also release caffeine into the tea.

Although widespread throughout the country now, spruce tea has its origins in the mountainous northern regions. When these areas were conquered many, many years ago they introduced the southern and coastal areas to the drink. It saw a significant spike in its popularity in the late 1800s when teabags started to be issued as part of army rations. Conscripts brought their love for spruce tea back to their civilian life when their conscription period was over.

Tea is a significant part of the average Hexastalian’s diet, with an average of 1.6 teabags being used per day, per Capita. It is most commonly consumed warm in the morning, then lukewarm to room temperature throughout the day.

Hongkong97

Registered

- Pronouns

- She/Her.

- TNP Nation

- Azxonia

So… why are Azxonians obsessed with soda?

In 1773, an Azxonian Doctor named Alín Vasku invented the world’s first commercial carbonated drink. Called “Alí Harz”, which roughly translates to Alín’s water, it was initially a commercial failure - only hanging around due to Alín’s personal health cult that were obsessed with the drink’s supposed health properties. However, in 1784, the drink skyrocketed in popularity with Azxonian nobles due to the King’s appointment of Alín as his personal doctor. Some of the wealthier among them began to experiment with the drink, adding flavouring to “Alín‘s water” in order to lessen the salty taste of the carbonated water. Overtime, these recipes began to evolve more and more, resulting in the creation of the first direct competitor to Alín - “Aktübarská” ( which translates to “October‘s taste” ) - in 1799.

Aktübarská differed significantly from Alín Harz ( now renamed to ”Harzatü Lafka” ) in that it was ostensibly marketed to the working class of Azxonia as a healthier alternative to alcohol. Much was made of it’s crisp apple and pear flavouring and it became an enormous success, edging out Alín Harz as the nation’s most popular soda. Although Alín Harz remained prevalent in the upper class of Azxonia, it was clear Aktübarská had cornered the domestic market and by 1842 had begun to slowly expand to nearby nations. However, it was significantly slowed by the death of it’s founder Jaküb Zataliki in 1845. His death created an enormous power vacuum, during which, a new company began to push it’s way to the top spot.

Farnüzak ( “Exotic” ), created by Jíorga Nadökuzalí in 1837, marketed itself to as many people as possible by marketing itself by using a wide variety of flavours that were rare or expensive in Azxonia - such as bananas, pomegranates or passion fruit. The reason that Jíorga could do this without bankrupting himself was due to his enormous fortune from a gigantic mining empire he had built and that he had begun to create a pharmaceutical company - during the creation of which, he had accidentally miscalculated the amount of greenhouses he’d need to grow medicinal plants - ending up with a surplus that he had no clue how to use. Until he realised he could instead grow exotic fruits - believing in the health benefits of soda and wanting to bring at least some of the luxuries he had to the people that worked for him. His timing could not have been better - the middle and upper class were in a frenzy after Colonel Juhaz Mazakil has published the stories of his adventures throughout the world and were itching to explore some of the world. A soda flavoured with exotic ( at least to Azxonians ) incredibly exotic and unique fruits.

By 1851 Aktübarská and Farnüzak were battling for control of the Azxonian soda market. By now, most bars throughout the country served soda alongside alcohol. Some had even fully converted to “Soda bars”, that refused to serve alcohol. Ever since, Azxonians have been among the largest soda drinkers in the world, drinking an approximate 97 litres of soda a year - a number that has steadily been rising over recent years, prompting the Azxonian government to begin discussing the introduction of a ”soda tax” to discourage overconsumption.

Oh. And also. Farnüzak won the ”soda wars” of the 1850s. They bought Aktübarská in 1964 and Harzatü Lafka in 1921.

In 1773, an Azxonian Doctor named Alín Vasku invented the world’s first commercial carbonated drink. Called “Alí Harz”, which roughly translates to Alín’s water, it was initially a commercial failure - only hanging around due to Alín’s personal health cult that were obsessed with the drink’s supposed health properties. However, in 1784, the drink skyrocketed in popularity with Azxonian nobles due to the King’s appointment of Alín as his personal doctor. Some of the wealthier among them began to experiment with the drink, adding flavouring to “Alín‘s water” in order to lessen the salty taste of the carbonated water. Overtime, these recipes began to evolve more and more, resulting in the creation of the first direct competitor to Alín - “Aktübarská” ( which translates to “October‘s taste” ) - in 1799.

Aktübarská differed significantly from Alín Harz ( now renamed to ”Harzatü Lafka” ) in that it was ostensibly marketed to the working class of Azxonia as a healthier alternative to alcohol. Much was made of it’s crisp apple and pear flavouring and it became an enormous success, edging out Alín Harz as the nation’s most popular soda. Although Alín Harz remained prevalent in the upper class of Azxonia, it was clear Aktübarská had cornered the domestic market and by 1842 had begun to slowly expand to nearby nations. However, it was significantly slowed by the death of it’s founder Jaküb Zataliki in 1845. His death created an enormous power vacuum, during which, a new company began to push it’s way to the top spot.

Farnüzak ( “Exotic” ), created by Jíorga Nadökuzalí in 1837, marketed itself to as many people as possible by marketing itself by using a wide variety of flavours that were rare or expensive in Azxonia - such as bananas, pomegranates or passion fruit. The reason that Jíorga could do this without bankrupting himself was due to his enormous fortune from a gigantic mining empire he had built and that he had begun to create a pharmaceutical company - during the creation of which, he had accidentally miscalculated the amount of greenhouses he’d need to grow medicinal plants - ending up with a surplus that he had no clue how to use. Until he realised he could instead grow exotic fruits - believing in the health benefits of soda and wanting to bring at least some of the luxuries he had to the people that worked for him. His timing could not have been better - the middle and upper class were in a frenzy after Colonel Juhaz Mazakil has published the stories of his adventures throughout the world and were itching to explore some of the world. A soda flavoured with exotic ( at least to Azxonians ) incredibly exotic and unique fruits.

By 1851 Aktübarská and Farnüzak were battling for control of the Azxonian soda market. By now, most bars throughout the country served soda alongside alcohol. Some had even fully converted to “Soda bars”, that refused to serve alcohol. Ever since, Azxonians have been among the largest soda drinkers in the world, drinking an approximate 97 litres of soda a year - a number that has steadily been rising over recent years, prompting the Azxonian government to begin discussing the introduction of a ”soda tax” to discourage overconsumption.

Oh. And also. Farnüzak won the ”soda wars” of the 1850s. They bought Aktübarská in 1964 and Harzatü Lafka in 1921.

Religion in Kaliva

Kaliva’s constitution guarantees full religious freedom, with the recognition or establishment of a state religion being prohibited. According to the results of the 2020 census, nearly four-tenths of the Kalivese population (38.1%) declared themselves not affiliated with any religious organizations. In a 2018 survey, 28% declared themselves “strongly religious,” 11% declared themselves “somewhat religious,” 18% declared themselves “partially religious,” 20% said they were not religious, and 15% identified themselves as atheists. Of the people who are affiliated with a religious organization, most are either Srutists or Messianists. Per the 2020 census, 31.9% of the population were Srutists and 27.1% of the population were Messianism (24.3% identified themselves as Courantists, 1.9% as Laurentists.) Other minor religions include Shaddaism (0.5% of the population), and a variety of indigenous religions, including Anantaism. Overall, between the 2010 and 2020 censuses, there has been a slight decline of Srutism (down from 34.2% to 31.9%), and a rise in the Messianist population (from 24.2% to 27.1%) and unaffiliated population (from 37.8% to 38.1%).

Ethnicity in Kaliva

Kaliva’s population is highly diverse, but research on Kalivese ethnicity has felt the impact of nationalist discourses on identity. Since the 1960s, the Kalivese government has promoted the view that all Kalivese are part of the Whespurashi community, within which they are distinguished only by degree of fluency in a non-Whespurashi language, and degree of adherence to religious customs. It was not until very recently that the Kalivese government began conducting surveys that considered the Mishras as a separate ethnicity from the Whespurashi and Vraspmi. Less numerous groups in Kaliva such as Ceretians and Prydanians are also accounted for, with numbers of around three and two percent each.

While Mishras are a prominent ethnic group in contemporary Kaliva, the subjective and ever-changing definition of this category have led to its estimations being imprecise, having been observed that many Kalivese do not identify as Mishras, favoring instead labels such as Whespurashi or Vraspmi due to having more consistent and "static" definitions. The total percentage of Kaliva’s Gotic Whespurashi peoples tends to vary depending on the criteria used by the government in its censuses: if single-selection racial self-identification is used, it is 45.2% and if people who consider themselves part Whespurashi are also included, it amounts to 73.2%. Nonetheless, all the censuses conclude that the majority of Kaliva’s Whespurashi population is concentrated in the central and southeastern areas of the country, with the highest percentages being found in Windermere (59% of the population), Mydia (48%), Kasamina (43%), Kosaria (39%), and Prinzland (37%).

Similarly to Mishra and Wespurashi peoples, estimates of the percentage of Syrixian-descended Kalivese (Vraspmi) vary considerably depending on the criteria used: if single-selection racial self-identification is used, it is 12.3% and if people who consider themselves part Vraspmi are also included, it amounts to 38.2%. Kaliva’s northeastern regions have the highest percentages of Vraspmi populations, with the majority of the people having either partial or predominant Syrixian ancestry.

With a population of 2,560,000, the Prinzish are the third largest ethnic minority in Kaliva, concentrated predominantly in western Prinzland and representing 9.3% of the country's population (41% in the Prinzland Region). The ethnicity of the Prinzish and the correct linguistic classification of their language remain somewhat sensitive and controversial. The Prinzish may be considered either ethnic Xentheridians or Xentheridian-speaking Whespurashics, but Prinzish nationalists maintain that Prinzish culture is distinctly different from both Xentheridia and Kaliva.

Smaller ethnic groups in Kaliva include Ceretians and Prydanians. Modern Nordic immigration began in the late 19th century, with Prydanians being the second-largest immigrant group. After the Prydanian Civil War broke out, Prydanian immigration would see a massive surge, as many Prydanians took refuge in Kaliva. The first Prydanians to come to Kaliva during the Civil War were often from Prydania’s educated upper and middle classes centered in Prydania’s capital, Beaconsfield. This has led to the city of Suravesta gaining the nickname, "Bjkanströnd" (Beacon’s Beach.) Outside of Saintonge and Goyanese, Kaliva is the largest recipient of Prydanian refugees on Eras.

Kaliva’s constitution guarantees full religious freedom, with the recognition or establishment of a state religion being prohibited. According to the results of the 2020 census, nearly four-tenths of the Kalivese population (38.1%) declared themselves not affiliated with any religious organizations. In a 2018 survey, 28% declared themselves “strongly religious,” 11% declared themselves “somewhat religious,” 18% declared themselves “partially religious,” 20% said they were not religious, and 15% identified themselves as atheists. Of the people who are affiliated with a religious organization, most are either Srutists or Messianists. Per the 2020 census, 31.9% of the population were Srutists and 27.1% of the population were Messianism (24.3% identified themselves as Courantists, 1.9% as Laurentists.) Other minor religions include Shaddaism (0.5% of the population), and a variety of indigenous religions, including Anantaism. Overall, between the 2010 and 2020 censuses, there has been a slight decline of Srutism (down from 34.2% to 31.9%), and a rise in the Messianist population (from 24.2% to 27.1%) and unaffiliated population (from 37.8% to 38.1%).

Ethnicity in Kaliva

Kaliva’s population is highly diverse, but research on Kalivese ethnicity has felt the impact of nationalist discourses on identity. Since the 1960s, the Kalivese government has promoted the view that all Kalivese are part of the Whespurashi community, within which they are distinguished only by degree of fluency in a non-Whespurashi language, and degree of adherence to religious customs. It was not until very recently that the Kalivese government began conducting surveys that considered the Mishras as a separate ethnicity from the Whespurashi and Vraspmi. Less numerous groups in Kaliva such as Ceretians and Prydanians are also accounted for, with numbers of around three and two percent each.