OPINION: Osborne's government is taking modernisation seriously; but has it gone out of their control?

A lifetime's worth of "stabilisation" morphed into managed decline under John Largan; the Osborne government's juncture has put it on a new path

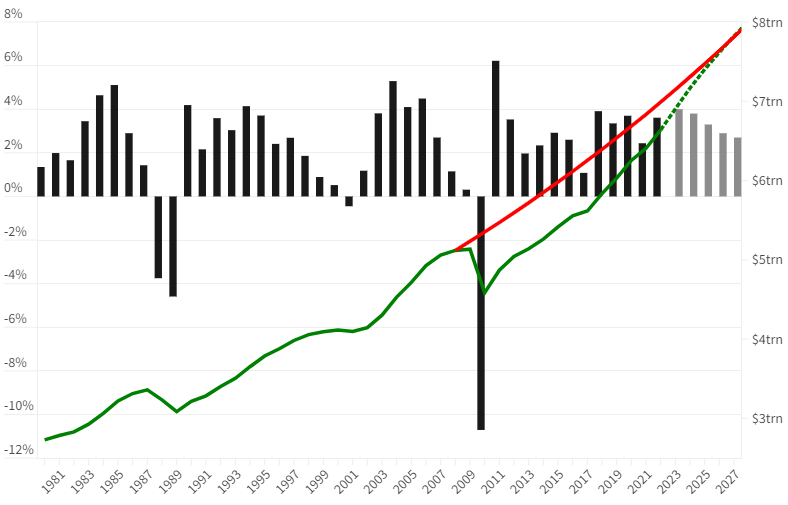

Esthursia was in a very dark place ten years ago, though we might not remember. It's easy to look back at the "large" growth that took place in Largan's tenure - even though it had more or less evaporated by the end, and most of it was a sudden but slowing recovery to the Einarsson-era financial crisis - but hard to remember just how poor a path forecasts were putting us on.

It's easy to remember the major areas of difference between the Newell, Holmfirth, Moore, Greenwood and Grantham governments, yet when Mark Willesden came into power in 2002, those differences didn't seem so stark. Willesden was a figure of the self-imposed centre - possibly the epitome of Esthursia in the late 20th century. An elderly gentleman, from a long line of increasingly highly-educated, service sector professionals - his father being in the same financial sector he entered in young age - who just happened to crash into politics as a middle-age venture, and never left it. Realistically, Mark Willesden could have served in any of the above governments - except perhaps David Holmfirth's, whose technocratic and left-wing reforms would have been far too much for him to stomach - quite happily. The main reason for that proved to be that all of them, again except Holmfirth's to an extent, were completely unwilling to alter the foundations of Esthursia's economy and society.

The reason for this? It seemed to work. One of the unsung heroes of financial growth was the Salisbury government, whose reforms between 1911 and 1916 gave birth to the Brough, and whose latter six years gave it enough guard rails to prevent it crashing off the cliff created by Salisbury's successor, warmongering James Thorne between 1922 and 1926. Even George Asmont's decision that these relatively new but now hefty and endangered financial institutions were too important and hopeful to leave down on the priority list rather than address quickly in his tenure was a sign of this culture already starting - yet his reforms would take near to a century to water down. By the time the Newell government came around, it had a lot more problems to deal with - what with 7 years of dictatorial wrecking-ball politics having just ended - and decided the existing guard rails, by this point over 40 years old in many places, were sturdy enough. Martha Grantham was born significantly after these guard rails were installed, yet by her tenure was already an elderly woman.

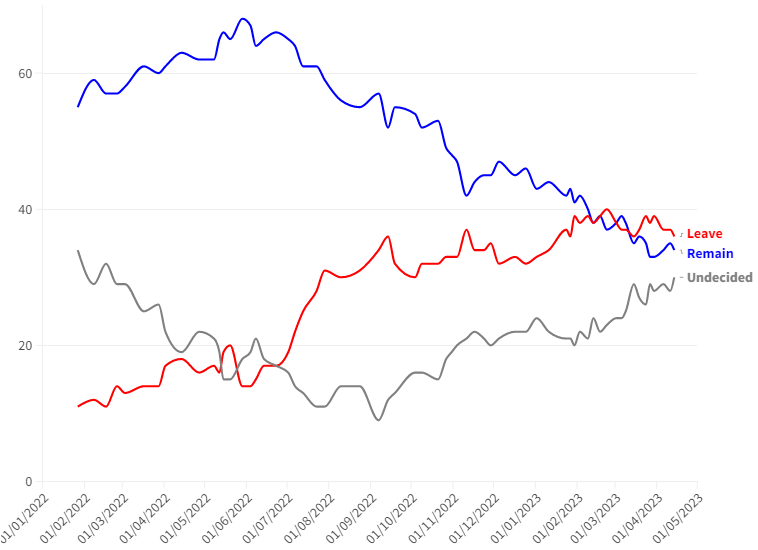

The 2000s therefore brought an uneasy consensus between the "left" and right. There is good reason to be skeptical about how influential the left truly was in this period - the Social Democrats' splinter in 2002 locked it out of power for a decade, and realistically Mark Willesden was centre to centre-right. Mark Willesden and Isaac Harding had a lot in common, but the key tenet of those was that the financial sector must be seen to grow a lot quicker than everything else. The civil service had little to no reforms between the 1940s and 2000s to restrict it, while falling pay and "market reforms" bleeding into it from the 1980s which had been more or less ignored by the 1990s Social Democrat governments had left educated elites more or less ignoring the public sector roles. Harding, by 2005, had however noticed that the warning signs had been flashing for quite some time - trade schools, investment programmes, and eventually a gradually tightening belt of austerity were the increasingly desperate actions of a government more and more constrained by its own goal not to enter managed decline. By 2009, the attempts to avoid this were already bringing it towards managed decline anyway; cue Tharbjorn Einarsson.

For all intents and purposes, Tharbjorn Einarsson was a poor Forethane. Yet he cannot be solely, or even primarily, blamed for the crisis that unfolded - because it was a long time coming. By 2009, when he took power, the economy was more or less already in technical recession. Not only that, but the government had been conducting austerity measures for three years, inflation was nearing the red zone, and interest rates had been creeping up. Behind the scenes, the financial sector's self-regulatory measures of the past decade or so, stalled by Granthamite reforms and released again in the 2000s, left the economy's stability - let alone growth, which had been lost already - dependent on credit, which itself was dependent on the indebted, many of whom could never pay back. Credit rating agencies were similarly either blind or deliberately ignorant - one is likely to think the second - towards this; staving off the inevitable had become a catch-22, since abandoning it would be an admission of corruption while also plunging the economy then and there, while maintaining it would be increasingly suspicious while also eroding their reputation. In the end, everything happened.

Of course, Einarsson's refusal to conduct managed decline in the same way Harding had was replaced with what could best be described as "setting fire to everything". His government set about making sure the economic damage was as deep as possible, pissing off workers so quickly that a General Strike had been pronounced within 12 months of his appointment, while simultaneously deregulating financial institutions beyond the point of no return. Now, housebuyers who couldn't afford their subprime loans were borrowing off of payday lenders, and then found themselves unable to pay a much larger bill in turn. Dancing money, jovial music and jaunty mascots on TV screens attempted to hide the astronomical yearly interest rate that entering contracts with them began.

It's easy to just leave this to this period - but this had become a clear trend. The early 1980s saw unsustainable growth followed by a sudden collapse. The 1990s saw unsustainable growth followed by stagnation. The 2000s saw unsustainable growth followed by a sudden collapse. Esthursia's economy had given way to the boom and bust cycle, and with two of those periods renowned for their rises in inequality, only the latter part of the cycle actually affected the average person. Not only did this leave many governments in a state of false security, luring them into believing they were far more revolutionary than they ever were before plunging their system off a financial cliff - either by political origin, such as Greenwood's inciting of a national strike and inflation crisis, or by economic, such as the pre-Einarsson austerity period - but it also repeatedly delayed reform. Either things were "going too well" to necessitate reform, or too badly to allow it.

When John Largan came to power in 2011, he found the nation bankrupt and although leaving the worst of its recession, forecasts were poor. Largan has reputed to have said the following weeks after entering office upon the INS' budget report:

Where's all the money gone?

The issue with John Largan became clear relatively quickly. Although he proved effective at emergency measures, and initial moves to (re-)regulate the financial sector while also keeping it from completely sinking under the weight of its own failures were critically important to stop the damage becoming permanent, he quickly became a leader of the late 20th century. The economy around him was changing, though; the importance of the Brough had been heavily dented by the Crash, with Brantley, Execester, Esthampton, Gloucester, Hereporth, Cambury, Rennezh, Strantglade, Tynwald and Fjarmagn all boasting new financial sectors with exponential growth mostly from the Brough's lost reputation and rising prices. The changes were so fundamental that it remains likely that Brantley will overtake Weskerby as the nation's most populous city within the next decades, and soon after the largest city economy.

It became clear by 2014 that Largan was more set on getting "back on track" than wondering why the train had derailed in the first place. People, this time, noticed; the initial promises and high sentiments were replaced with the same-old feelings that wages, living standards, productivity, capacity, and everything inbetween all seemed to be stagnant and non-moving. It became inevitable, when the Largan government unexpectedly survived - albeit with wounds it couldn't then outlive - the election, that the Social Democrats would finally appoint a new leader. Fears of a lost decade between 2012 and 2022 were sown, with forecasts in 2014 putting average economic growth below 2% for that period's predictions, denting Largan's reputation even further.

This new leader proved to be Harold Osborne. John Largan's shift to the centre-left away from Mark Willesden had earnt the ire of many centrists and returned many leftists to the party with the hope of appointing a leftist - Osborne, although at this point not as overtly socialist as many in this faction would want, became their best chance of this process continuing. This proved more successful than any of them may have hoped. He also proved willing to conduct constitutional change from day one, and equally willing to tackle what was fuelling economic stagnation of this severity.

Even with a majority of near-zero, Osborne's government set about undoing the legacy of a generation of politicians. A few clear oddities stood out - appointing Jeremy Wilson, and a lot of other Progressive hardliners, to top offices. Wilson, although as a personality divisive and increasingly populist - culminating in his own downfall - was potentially the first high-ranking politician to grasp just how pointlessly stagnant the results of Esthursia's long-term policies had been. The economic priorities shifted from preserving finance and property ownership, to redefining it; though realistically, the top two priorities of the Osborne government have been redistribution and labour productivity - the latter dependent on working rights, but now increasingly not just that.

Possibly, even without Wilson in a high position, Harold Osborne has warmed to this new policy programme. Although it's easy to notice Osborne's public shift between refusing to call himself a socialist, and openly embracing it, as well as his appointment of a socialist to replace Wilson rather than a moderate or soft-leftist - maybe the most clear juncture was the Code of Atlish Law, per chance. Bear with me; but the main reason for this was that it finally recognised that in this case, it wasn't the regulation itself that was holding Esthursia back, but the fact it was so outdated, unviable, inconsistent and scattered that it wasn't functioning. It had taken a hundred years for a government to finally look back to the Salisbury government, maybe even more so than the Asmont-era government on this regard, and do anything but maintain and preserve the institutions it created, rather than reform them.

The Osborne government's record has been quietly accomplished - Esthursia's soft power has steadily grown, while its economic trajectory has more or less changed course from the perma-stagnation mused about in the depths of 2014. The civil service's tendency to outsource - with one think tank paid to work out how to reduce the amount of think tanks involved in government symbolising exactly how deep-rooted this culture of faux-technocracy has become - and its failure to entice the thinkers of the day have all slowly held Esthursia's policy programmes back, yet new democracy measures and reforms to the service are bringing them back, going on a positive trajectory for the first time in maybe a century and a half. The indices that were pointing towards managed decline for Harding and Largan - productivity, capacity, inequality, wage growth - all were now in the green, albeit more subtly than Osborne had hoped - because even Osborne has not fully grasped just how deep-rooted the issues lie.

The absurdity of all this becomes clear in hindsight - many of the economists seen as consensus-building were long, long dead by the time Osborne came to power and did away with much of their thinking. Gordon Hewitt, possibly the most prominent economist associated with the Salisbury-era reforms, died in 1927. John Marston-Smythe, an economist Salisbury drew on, was often cited by the Harding government; he died in

1859, and his teachings were often seen as old hat even by the mid-19th century Liberal governments

. The idea that their worldviews, and their prospective ideas - for they were ideas, not institutions, at the points they were conceived - are congruent to a world one-hundred, two-hundred years after they lived - that's exactly the fallacy that kept Esthursia on the path it was on.

The issue with all this? It promotes anger, populism, even now, because few politicians recognise the problem properly. Osborne is on the fringes of mainstream social democracy, increasingly leaning over the ledge - and Wilson, a man increasingly seen to be the party's future thanks to his iron grip on the growing left fringe, is well away from that ledge. The failure of mainstream politics to address long-term fundamental issues with Esthursian economics and politics, from its centralised elitist education which still remains self-governing even under the Osborne government, to its dependence on finance to keep going, and until recently its failure to address wage stagnation despite economic growth, have all fuelled decades of polarisation. Greenwood's trade union clampdowns, Einarsson's tenure, Osborne and Wilson rising in their ranks, all easily attributable - the period in the 1970s, by contrast, proved critical to boost Greenwood's economic record by fuelling capital investment that only really kicked into gear when Holmfirth left power; and further prevented the need for him to lurch any further right. Maybe even the miasma of stagnation and lack of new ideas or innovation in the Workers' Union in the late 1940s left a certain path to power for Olafn Arbjern in 1950; and with Wilson's convincing speeches decrying exactly this institutional stigma to reforming key issues that left Esthursia on a path of unsustainable growth, then managed decline, repeatedly, it seems clear that his path to power is just as apparent.

Wilson's rise to his current position already seems to be ominous. He controls major cabinet positions - and is significantly more moderate than many of those he appointed to those positions - and the party's membership is increasingly sympathetic to his New Left ideology, merging together a refusal to endorse pacifism with economically socialist, perhaps verging on collectivist, policies. As Osborne tends left, and the party caucus follows suit each electoral cycle, his ability to lead a government appears less and less far-fetched than many initially thought when he fell from his position in 2017. Osborne's grip on his party may not be slipping yet, but the party is now as left-wing as he is for the first time ever, and maybe even be accelerating away from him; it's hard to tell where it might be in three years, but his musings around retirement - despite only being 53 this year, and 55 at the 2026 election - are suggestive that he's had enough... and equally suggestive are Wilson's manoeuvres. There remain other successors - Lauren Bowen, his successor, seems most obvious - but it is easy to speculate that Bowen would be just as populist as Wilson, but less economically radical.

Osborne's sacrifices of centrism may have also sacrificed anti-populism; despite his own politics. He remains a technocratic yet down-to-earth leader in his political style - a man from a family of urban industry, as opposed to generations of mostly (except Grantham, Moore and Holmfirth) finance-derived or otherwise elitist leaders - yet he appears to have viewed the sacrifice of moderates' public persona as "level-headed" (knowing that this is synonymous with refusal to adhere to his increasingly diverging reforms) over leftists' populist nature, especially with the in-party New Left refusing to align with Green-Left pacifism against his own hawkish policy on military and foreign relations (if not outdoing him entirely), and gambled his government on it. This may have been a success for his current leadership, effectively guaranteeing the passage of his reforms, but its result proved to be securing Wilson's deputy position, allowing him to continue to appoint Redethanes, all while the party membership and administration eschews its old moderate stances. The party, by the time the next decade starts, is likely to be more democratic socialist than social democratic - a clear overshoot from Largan's initial juncture from Third Way centre-right politics.

The main dividend of this gamble appears to be the staving off of managed decline - this remains a reality, though, as Esthursian demographics shift towards an aging, and eventually declining population. Yet, this may fuel the desire for radical politicians like Wilson further, who are willing to make even larger gambles as well as to eschew the consensus even more blatantly in an attempt to both claim the rewards of the first government to recognise the importance of constitutional reform in the economy in many ways, and at the same time therefore earn the trust of the population.

Let's hope he doesn't go down the same path, should he reach power - or we might be in for another century of this. The Osborne government may have tackled many key fundamental issues, taken Esthursia off the path of excessive boom and bust somewhat, and certainly off the path of managed decline, but it may be too little, too late to stop the rise of a left-populist just yet. Perhaps, there remains time for the old style of politics just yet, if Manning fosters unity in the Moderates enough, or if Osborne resigns and a successor - Wilson, Bowen or otherwise - proves an ineffective campaigner. Or maybe, just maybe, they were in time to prevent any of these questions needing to be asked.