The Royal Air Force

Chapter 1 ................ The Development of the Royal Air Force

Chapter 2 ................ The Royal Air Force - Organisation

Chapter 3 ................ Security

CHAPTER 1

DEVELOPMENT OF THE ROYAL AIR FORCE

The realisation that Britain was falling behind in the aviation race came towards the end of 1911 then the British Army and Royal Navy between them could muster approximately three airships and between four and eight aircraft with 19 competent aviators. By comparison France had over 200 aircraft and 263 aviators, whilst Germany mustered a fleet of 30 airships. Something had to be done. The Committee of Imperial Defence set up a technical sub-committee (a typical British reaction) to look into British military aviation. But this committee outperformed most of its type: its findings were speedily formulated with complete agreement, and issued in a White Paper in 1912 which set up a unified flying service called The Flying Corps. However, His Majesty the King decided that as flying, let alone fighting in the air, was a hazardous occupation, he would issue a royal warrant to grant it the title The Royal Flying Corps (RFC). This Royal Flying Corps would have a Central Flying School, a Military Wing to work with the Army, a Naval Wing to work with the

Navy, a Reserve, and the Royal Aircraft Factory (RAF, at Farnborough) to build its military aircraft.

Except for the use of balloons for reconnaissance, military aviation in the United Kingdom started in May 1912, with the formation of the Royal Flying Corps(RFC). All pilots were then trained at the central flying school at Upavon. The

aircraft were unarmed and were intended to be used for reconnaissance in support of military and naval operations.

From the start, the Admiralty had no intention of allowing its air affairs to escape from under its own control, and in fact the name Royal Flying Corps, Naval Wing, never really appeared anywhere other than on a few official documents. A new title, Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS), gained rapid currency and, by the time that World War I broke out in August 1914, it had received official sanction. With only a token participation in the Central Flying School, the Admiralty carried on with its own aviation affairs, training its own aviators and ordering its own aircraft direct from the

manufacturers, thereby spurning most of the products of the Royal Aircraft Factory at Farnborough.

In June 1914, it was decided that the use of aircraft in support of naval operations posed special problems and the navy broke away from the RFC to forma Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS).

On 19th August 1914 the RFC began its air war with two reconnaissances, one by Captain Philip Joubert de la Ferte of No 3 Squadron in a Bleriot, and the other by Lieutenant G W Mapplebeck of No 4 Squadron in a BE2. The value of aerial reconnaissance was quickly made crystal clear with the German advance and the Allies hurried withdrawal, the RFC squadrons keeping the troops posted with information on the Germans’ latest strength, location and movement. Allied casualties could well have been higher without the advantage of this new method of reconnaissance.

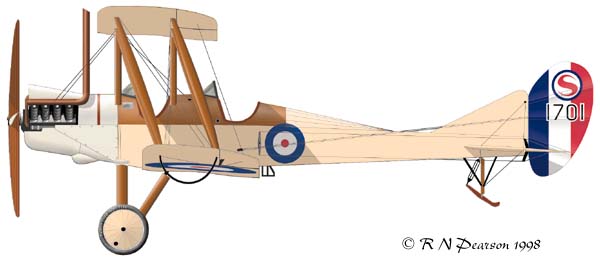

RAF BE2c 1701 "Victoria Hong Kong No.2" No.4 Sqn RFC

By 1915 the war in the air was moving into a different phase - the joy of simply sitting up in the air watching the land battle below had been spoilt by one or two pilots taking their revolvers aloft with them and taking pot shots at the enemy’s aircraft. By October the French had already armed a Voisin with a machine-gun and shot down a German reconnaissance aircraft - war in the air was on.

As early as March 1915 the assault on Neuve Chapelle benefitted from the availability of tactical maps based solely on aerial photographs. Up until now the RFC had largely been observers of the battle scene, but in that same month the BE2s and other suitable aircraft were bombed up and sent in to attack behind the enemy lines to prevent reserves from moving up to the front line.

The leisurely days of aerial warfare were soon over for ever, and the most spectacular symbol of this change was the Fokker Eindecker (monoplane). Both sides in the struggle had progressed towards scouts armed with machine-guns for the express purpose of aerial combat, but none so far had approached the effectiveness of the Fokker Monoplane. This aircraft could have fought with the British for Anthony Fokker, a Dutchman, had offered his services first to the

Allies, only to be spurned. He then moved to Germany where his Monoplane was evolved being the first production aircraft successfully to solve the problem of firing the machine-gun through the propeller.

The aircraft were still used mainly for reconnaissance work and it was not until the Germans began to use fighter aircraft to shoot down our reconnaissance machines that we countered with our own British fighters to protect them. The introduction of fighter aircraft on both sides led to the now legendary battles over the western front in which men like Ball, McCudden, Mannock, Von Richthofen, Immelmann and Boelcke fought for air superiority.

By 1916, as a result of early Zeppelin raids, it was quickly realised that aircraft could also be used for bombing, and both the RFC and RNAS commenced bombing attacks against Germany. By 1917 the German Air Force used bomber aircraft to attack this country. This bombing and counter-bombing was to play a significant part in the formation of the Royal Air Force and in fact spurred the Government into action. A committee under General Smuts was set up and its recommendations resulted in the formation of the Air Council and the establishment of the Air Ministry.

On the 1st April, 1918, the Royal Air Force was born through the malgamation of the existing RFC and RNAS.

No 66 Squadron of the RFC flew the Sopwith Pup, with great success, in France in 1917

To Be Continued