Geography

Main article:

Geography of Myanmar

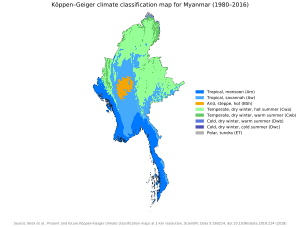

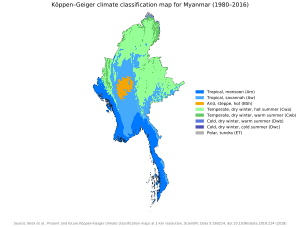

Myanmar map of Köppen climate classification.

Myanmar has a total area of 678,500 square kilometres (262,000 sq mi). It lies between latitudes

9° and

29°N, and longitudes

92° and

102°E. Myanmar is bordered in the northwest by the

Chittagong Division of

Bangladesh and the

Mizoram, Manipur,

Nagaland and

Arunachal Pradesh states of India. Its north and northeast border is with the

Tibet Autonomous Region and

Yunnan for a Sino-Myanmar border total of 2,185 km (1,358 mi). It is bounded by

Laos and

Thailand to the southeast. Myanmar has 1,930 km (1,200 mi) of contiguous coastline along the

Bay of Bengal and

Andaman Sea to the southwest and the south, which forms one quarter of its total perimeter.

[2]

In the north, the

Hengduan Mountains form the border with China.

Hkakabo Razi, located in

Kachin State, at an elevation of 5,881 metres (19,295 ft), is the highest point in Myanmar.

[157] Many mountain ranges, such as the

Rakhine Yoma, the

Bago Yoma, the

Shan Hills and the

Tenasserim Hills exist within Myanmar, all of which run north-to-south from the

Himalayas.

[158] The mountain chains divide Myanmar's three river systems, which are the

Irrawaddy,

Salween (Thanlwin), and the

Sittaung rivers.

[159] The Irrawaddy River, Myanmar's longest river at nearly 2,170 kilometres (1,348 mi), flows into the

Gulf of Martaban. Fertile plains exist in the valleys between the

mountain chains.

[158] The majority of Myanmar's population lives in the

Irrawaddy valley, which is situated between the

Rakhine Yoma and the

Shan Plateau.

Administrative divisions

Main article:

Administrative divisions of Myanmar

Myanmar is divided into seven states (ပြည်နယ်) and seven regions (တိုင်းဒေသကြီး), formerly called divisions.

[160] Regions are predominantly Bamar (that is, mainly inhabited by Myanmar's dominant ethnic group). States, in essence, are regions that are home to particular ethnic minorities. The administrative divisions are further subdivided into

districts, which are further subdivided into townships,

wards, and villages.

Below are the number of districts, townships, cities/towns, wards, village groups and villages in each division and state of Myanmar as of 31 December 2001:

[161]

Climate

Main article:

Climate of Myanmar

Much of the country lies between the

Tropic of Cancer and the

Equator. It lies in the

monsoon region of Asia, with its coastal regions receiving over 5,000 mm (196.9 in) of rain annually. Annual

rainfall in the

delta region is approximately 2,500 mm (98.4 in), while average annual rainfall in the dry zone in central Myanmar is less than 1,000 mm (39.4 in). The northern regions of Myanmar are the coolest, with average temperatures of 21 °C (70 °F). Coastal and delta regions have an average maximum temperature of 32 °C (89.6 °F).

[159]

Previously and currently analysed data, as well as future projections on changes caused by climate change predict serious consequences to development for all economic, productive, social, and environmental sectors in Myanmar.

[162] In order to combat the hardships ahead and do its part to help

combat climate change Myanmar has displayed interest in expanding its use of renewable energy and lowering its level of carbon emissions. Groups involved in helping Myanmar with the transition and move forward include the

UN Environment Programme, Myanmar Climate Change Alliance, and the

Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation which directed in producing the final draft of the Myanmar national climate change policy that was presented to various sectors of the Myanmar government for review.

[163]

In April 2015, it was announced that the

World Bank and Myanmar would enter a full partnership framework aimed to better access to electricity and other basic services for about six million people and expected to benefit three million pregnant woman and children through improved health services.

[164] Acquired funding and proper planning has allowed Myanmar to better prepare for the impacts of climate change by enacting programs which teach its people new farming methods, rebuild its infrastructure with materials resilient to natural disasters, and transition various sectors towards reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

[165]

Biodiversity

Main article:

Wildlife of Myanmar

The limestone landscape of

Kayin State

Further information:

Deforestation in Myanmar and

List of protected areas of Myanmar

Myanmar is a

biodiverse country with more than 16,000

plant, 314

mammal, 1131

bird, 293

reptile, and 139

amphibian species, and 64 terrestrial

ecosystems including tropical and subtropical vegetation, seasonally inundated wetlands, shoreline and tidal systems, and alpine ecosystems. Myanmar houses some of the largest intact natural ecosystems in

Southeast Asia, but the remaining ecosystems are under threat from land use intensification and over-exploitation. According to the

IUCN Red List of Ecosystems categories and criteria more than a third of Myanmar's land area has been converted to

anthropogenic ecosystems over the last 2–3 centuries, and nearly half of its ecosystems are threatened. Despite large gaps in information for some ecosystems, there is a large potential to develop a comprehensive

protected area network that protects its terrestrial biodiversity.

[166]

Myanmar continues to perform badly in the global

Environmental Performance Index (EPI) with an overall ranking of 153 out of 180 countries in 2016; among the worst in the

South Asian region, only ahead of

Bangladesh and

Afghanistan. The EPI was established in 2001 by the

World Economic Forum as a global gauge to measure how well individual countries perform in implementing the United Nations'

Sustainable Development Goals. The environmental areas where Myanmar performs worst (i.e. highest ranking) are

air quality (174), health impacts of

environmental issues (143) and

biodiversity and

habitat (142). Myanmar performs best (i.e. lowest ranking) in

environmental impacts of fisheries (21) but with declining

fish stocks. Despite several issues, Myanmar also ranks 64 and scores very good (i.e. a high percentage of 93.73%) in environmental effects of the agricultural industry because of an excellent management of the

nitrogen cycle.

[167][168] Myanmar is one of the most highly vulnerable countries to

climate change; this poses a number of social, political, economic and foreign policy challenges to the country.

[169] The country had a 2019

Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 7.18/10, ranking it 49th globally out of 172 countries.

[170]

Myanmar's slow economic growth has contributed to the preservation of much of its environment and ecosystems.

Forests, including dense tropical growth and valuable

teak in lower Myanmar, cover over 49% of the country, including areas of

acacia,

bamboo,

ironwood and

Magnolia champaca.

Coconut and

betel palm and rubber have been introduced. In the

highlands of the north, oak, pine and various rhododendrons cover much of the land.

[171]

Heavy logging since the new 1995 forestry law went into effect has seriously reduced forest area and wildlife habitat.

[172] The lands along the coast support all varieties of tropical fruits and once had large areas of

mangroves although much of the protective mangroves have disappeared. In much of central Myanmar (the dry zone),

vegetation is sparse and stunted.

Typical jungle animals, particularly

tigers, occur sparsely in Myanmar. In upper Myanmar, there are

rhinoceros,

wild water buffalo,

clouded leopard,

wild boars,

deer,

antelope, and

elephants, which are also tamed or bred in captivity for use as work animals, particularly in the

lumber industry. Smaller mammals are also numerous, ranging from

gibbons and

monkeys to

flying foxes. The abundance of

birds is notable with over 800 species, including

parrots,

myna,

peafowl,

red junglefowl,

weaverbirds,

crows,

herons, and

barn owl. Among reptile species there are

crocodiles,

geckos,

cobras,

Burmese pythons, and

turtles. Hundreds of species of freshwater fish are wide-ranging, plentiful and are very important food sources.

[173]

Government and politics

Head of Government, Deputy Head of Government, and acting Head of State

Myanmar operates

de jure as a

unitary assembly-independent republic under its

2008 constitution. But in February 2021, the civilian government led by

Aung San Suu Kyi, was deposed by the

Tatmadaw. In February 2021,

Myanmar military declared a one-year state emergency and First Vice President

Myint Swe became the

Acting President of Myanmar and handed the power to the

Commander-in-Chief of Defence Services Min Aung Hlaing and he assumed the role

Chairman of the State Administration Council, then

Prime Minister. The

President of Myanmar acts as the

de jure head of state and the

Chairman of the State Administration Council acts as the

de facto head of government.

[174]

Assembly of the Union

Assembly of the Union (Pyidaungsu Hluttaw)

The constitution of Myanmar, its third since independence, was drafted by its military rulers and published in September 2008. The country is governed as a

parliamentary system with a

bicameral legislature (with an executive

president accountable to the legislature), with 25% of the legislators appointed by the military and the rest elected in general elections.

The legislature, called the

Assembly of the Union, is bicameral and made up of two houses: the 224-seat upper

House of Nationalities and the 440-seat lower

House of Representatives. The upper house consists 168 members who are directly elected and 56 who are appointed by the

Burmese Armed Forces. The lower house consists of 330 members who are directly elected and 110 who are appointed by the armed forces.

Political culture

The major political parties are the

National League for Democracy and the

Union Solidarity and Development Party.

Myanmar's army-drafted constitution was approved in a

referendum in May 2008. The results, 92.4% of the 22 million voters with an official turnout of 99%, are considered suspect by many international observers and by the National League of Democracy with reports of widespread

fraud, ballot stuffing, and voter intimidation.

[175]

The

elections of 2010 resulted in a victory for the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party. Various foreign observers questioned the fairness of the elections.

[176][177][178] One criticism of the election was that only government-sanctioned political parties were allowed to contest in it and the popular

National League for Democracy was declared illegal.

[179] However, immediately following the elections, the government ended the house arrest of the democracy advocate and leader of the National League for Democracy,

Aung San Suu Kyi,

[180] and her ability to move freely around the country is considered an important test of the military's movement toward more openness.

[179] After unexpected

reforms in 2011,

NLD senior leaders have decided to register as a political party and to field candidates in future by-elections.

[181]

Myanmar's political history is underlined by its struggle to establish democratic structures amidst conflicting factions. This political transition from a closely held military rule to a free democratic system is widely believed to be determining the future of Myanmar. The resounding victory of

Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy in the 2015 general election raised hope for a successful culmination of this transition.

[182][183]

Myanmar rates as a corrupt nation on the

Corruption Perceptions Index with a rank of 130th out of 180 countries worldwide, with 1st being least corrupt, as of 2019.

[184]

Foreign relations

Main article:

Foreign relations of Myanmar

Myanmar President Thein Sein meets US President

Barack Obama in

Yangon, 2012

Though the country's foreign relations, particularly with

Western nations, have historically been strained, the situation has markedly improved since the reforms following the 2010 elections. After years of diplomatic isolation and economic and military sanctions,

[185] the United States relaxed curbs on foreign aid to Myanmar in November 2011

[117] and announced the resumption of diplomatic relations on 13 January 2012

[186] The

European Union has placed sanctions on Myanmar, including an

arms embargo, cessation of

trade preferences, and suspension of all aid with the exception of

humanitarian aid.

[187]

The former

Secretary-General of the United Nations,

U Thant (1961–1971)

Sanctions imposed by the United States and European countries against the former military government, coupled with boycotts and other direct pressure on corporations by supporters of the democracy movement, have resulted in the withdrawal from the country of most U.S. and many European companies.

[188] On 13 April 2012,

British Prime Minister David Cameron called for the economic sanctions on Myanmar to be suspended in the wake of the pro-democracy party gaining 43 seats out of a possible 45 in the 2012 by-elections with the party leader,

Aung San Suu Kyi becoming a member of the Burmese parliament.

[189]

Despite Western isolation, Asian corporations have generally remained willing to continue investing in the country and to initiate new investments, particularly in natural resource extraction. The country has close relations with neighbouring India and China with several Indian and Chinese companies operating in the country. Under India's

Look East policy, fields of co-operation between India and Myanmar include

remote sensing,

[190] oil and gas exploration,

[191] information technology,

[192] hydropower

[193] and construction of ports and buildings.

[194]

In 2008, India suspended military aid to Myanmar over the issue of human rights abuses by the ruling junta, although it has preserved extensive commercial ties, which provide the regime with much-needed revenue.

[195] The thaw in relations began on 28 November 2011, when Belarusian Prime Minister

Mikhail Myasnikovich and his wife Ludmila arrived in the capital, Naypyidaw, the same day as the country received a visit by U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, who also met with pro-democracy opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi.

[196] International relations progress indicators continued in September 2012 when Aung San Suu Kyi visited the United States

[197] followed by Myanmar's reformist president visit to the

United Nations.

[198]

In May 2013, Thein Sein became the first Myanmar president to visit the

White House in 47 years; the last Burmese leader to visit the White House was

Ne Win in September 1966. President

Barack Obama praised the former general for political and economic reforms and the cessation of tensions between Myanmar and the United States. Political activists objected to the visit because of concerns over human rights abuses in Myanmar, but Obama assured Thein Sein that Myanmar will receive U.S. support. The two leaders discussed the release of more political prisoners, the institutionalisation of political reform and the rule of law, and ending ethnic conflict in Myanmar—the two governments agreed to sign a

bilateral trade and investment framework agreement on 21 May 2013.

[199]

In June 2013, Myanmar held its first ever summit, the

World Economic Forum on East Asia 2013. A regional spinoff of the annual

World Economic Forum in

Davos, Switzerland, the summit was held on 5–7 June and attended by 1,200 participants, including 10 heads of state, 12 ministers and 40 senior directors from around the world.

[200]

Military

Main article:

Armed forces of Myanmar

A

Myanmar Air Force Mikoyan MiG-29 multirole fighter

Myanmar has received extensive military aid from China in the past.

[201] Myanmar has been a member of ASEAN since 1997. Though it gave up its turn to hold the ASEAN chair and host the

ASEAN Summit in 2006, it chaired the forum and hosted the summit in 2014.

[202] In November 2008, Myanmar's political situation with neighbouring Bangladesh became tense as they began searching for natural gas in a disputed block of the Bay of Bengal.

[203] Controversy surrounding the Rohingya population also remains an issue between Bangladesh and Myanmar.

[204]

Myanmar's armed forces are known as the

Tatmadaw, which numbers 488,000. The Tatmadaw comprises the

Army, the

Navy, and the

Air Force. The country

ranked twelfth in the world for its number of active troops in service.

[30] The military is very influential in Myanmar, with all top cabinet and ministry posts usually held by military officials. Official figures for military spending are not available. Estimates vary widely because of uncertain exchange rates, but Myanmar's military forces' expenses are high.

[205] Myanmar imports most of its weapons from Russia, Ukraine, China and India.

Myanmar is building a research

nuclear reactor near

Pyin Oo Lwin with help from Russia. It is one of the signatories of the nuclear

non-proliferation pact since 1992 and a member of the

International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) since 1957. The military junta had informed the IAEA in September 2000 of its intention to construct the reactor.

[206][207] In 2010 as part of the Wikileaks leaked cables, Myanmar was suspected of using North Korean construction teams to build a fortified surface-to-air missile facility.

[208] As of 2019, the United States

Bureau of Arms Control assessed that Myanmar is not in violation of its obligations under the

Non-Proliferation Treaty but that the Myanmar government had a history of non-transparency on its nuclear programs and aims.

[209]

Until 2005, the

United Nations General Assembly annually adopted a detailed resolution about the situation in Myanmar by consensus.

[210][211][212][213] But in 2006 a divided United Nations General Assembly voted through a resolution that strongly called upon the government of Myanmar to end its systematic violations of human rights.

[214] In January 2007, Russia and China vetoed a draft resolution before the

United Nations Security Council[215] calling on the government of Myanmar to respect human rights and begin a democratic transition. South Africa also voted against the resolution.

[216]

Human rights and internal conflicts

Main articles:

Human rights in Myanmar and

Internal conflict in Myanmar

Map of conflict zones in Myanmar.

States and regions affected by fighting during and after 1995 are highlighted in yellow.

There is consensus that the former military regime in Myanmar (1962–2010) was one of the world's most repressive and abusive regimes.

[217][218] In November 2012,

Samantha Power, Barack Obama's Special Assistant to the President on Human Rights, wrote on the White House blog in advance of the president's visit that "Serious human rights abuses against civilians in several regions continue, including against women and children."

[103] Members of the United Nations and major international human rights organisations have issued repeated and consistent reports of widespread and systematic human rights violations in Myanmar. The United Nations General Assembly has repeatedly

[219] called on the Burmese military junta to respect human rights and in November 2009 the General Assembly adopted a resolution "strongly condemning the ongoing systematic violations of human rights and fundamental freedoms" and calling on the Burmese military regime "to take urgent measures to put an end to violations of international human rights and humanitarian law."

[220]

International human rights organisations including

Human Rights Watch,

[221] Amnesty International[222] and the

American Association for the Advancement of Science[223] have repeatedly documented and condemned widespread human rights violations in Myanmar. The

Freedom in the World 2011 report by

Freedom House notes, "The military junta has ... suppressed nearly all basic rights; and committed human rights abuses with impunity." In July 2013, the

Assistance Association for Political Prisoners indicated that there were approximately 100 political prisoners being held in Burmese prisons.

[224][225][226][227] Evidence gathered by a British researcher was published in 2005 regarding the extermination or "Burmisation" of certain ethnic minorities, such as the

Karen,

Karenni and

Shan.

[228]

Mae La camp

Mae La camp,

Tak, Thailand, one of the largest of nine

UNHCR camps in Thailand

[229]

Based on the evidence gathered by Amnesty photographs and video of the ongoing armed conflict between the Myanmar military and the

Arakan Army (AA), attacks escalated on civilians in Rakhine State. Ming Yu Hah,

Amnesty International's Deputy Regional Director for Campaigns said, the

UN Security Council must urgently refer the situation in Myanmar to the

International Criminal Court.

[230] The military is notorious for rampant use of sexual violence.

[13]

Child soldiers

Child soldiers were reported in 2012 to have played a major part in the Burmese Army.

[231] The Independent reported in June 2012 that "Children are being sold as conscripts into the Burmese military for as little as $40 and a bag of rice or a can of petrol."

[232] The UN's Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict,

Radhika Coomaraswamy, who stepped down from her position a week later, met representatives of the government of Myanmar in July 2012 and stated that she hoped the government's signing of an action plan would "signal a transformation."

[233] In September 2012, the Myanmar Armed Forces released 42 child soldiers, and the

International Labour Organization met with representatives of the government as well as the

Kachin Independence Army to secure the release of more child soldiers.

[234] According to Samantha Power, a U.S. delegation raised the issue of child soldiers with the government in October 2012. However, she did not comment on the government's progress towards reform in this area.

[103]

Slavery and human trafficking

Further information:

Sex trafficking in Myanmar

Forced labour,

human trafficking, and

child labour are common in Myanmar.

[235][236] In 2007 the international movement to defend women's human rights issues in Myanmar was said to be gaining speed.

[237] Human trafficking happens mostly to women who are unemployed and have low incomes. They are mainly targeted or deceived by brokers into making them believe that better opportunities and wages exist for them abroad.

[238] In 2017, the government reported investigating 185 trafficking cases. The government of Burma makes little effort to eliminate human trafficking. Burmese armed forces compel troops to acquire labour and supplies from local communities. The

U.S. State Department reported that both the government and

Tatmadaw were complicit in sex and labour trafficking.

[239] Women and girls from all

ethnic groups and foreigners have been victims of sex trafficking in Myanmar.

[231] They are forced into prostitution, marriages, and or pregnancies.

[240][241]

Genocide allegations and crimes against Rohingya people

Displaced

Rohingya people of Myanmar

[242][243]

See also:

Rohingya conflict,

2013 Myanmar anti-Muslim riots, and

Rohingya genocide

The

Rohingya people have consistently faced human rights abuses by the Burmese regime that has refused to acknowledge them as Burmese citizens (despite some of them having lived in Burma for over three generations)—the Rohingya have been denied Burmese citizenship since the enactment of a

1982 citizenship law.

[244] The law created three categories of citizenship: citizenship, associate citizenship, and naturalised citizenship. Citizenship is given to those who belong to one of the national races such as Kachin, Kayah (Karenni), Karen, Chin, Burman, Mon, Rakhine, Shan, Kaman, or Zerbadee. Associate citizenship is given to those who cannot prove their ancestors settled in Myanmar before 1823 but can prove they have one grandparent, or pre-1823 ancestor, who was a citizen of another country, as well as people who applied for citizenship in 1948 and qualified then by those laws. Naturalised citizenship is only given to those who have at least one parent with one of these types of Burmese citizenship or can provide "conclusive evidence" that their parents entered and resided in Burma prior to independence in 1948.

[245] The Burmese regime has attempted to forcibly expel Rohingya and bring in non-Rohingyas to replace them

[246]—this policy has resulted in the expulsion of approximately half of the 800,000

[247] Rohingya from Burma, while the Rohingya people have been described as "among the world's least wanted"

[248] and "one of the world's most persecuted minorities."

[246][249][250] But the origin of the "most persecuted minority" statement is unclear.

[251]

Rohingya are not allowed to travel without official permission, are banned from owning land, and are required to sign a commitment to have no more than two children.

[244] As of July 2012, the Myanmar government does not include the Rohingya minority group—classified as

stateless Bengali Muslims from Bangladesh since 1982—on the government's list of more than 130 ethnic races and, therefore, the government states that they have no claim to Myanmar citizenship.

[252]

In 2007 German professor

Bassam Tibi suggested that the Rohingya conflict may be driven by an Islamist political agenda to impose religious laws,

[253] while non-religious causes have also been raised, such as a lingering resentment over the violence that occurred during the

Japanese occupation of Burma in World War II—during this time period the British allied themselves with the Rohingya

[254] and fought against the

puppet government of Burma (composed mostly of Bamar Japanese) that helped to establish the

Tatmadaw military organisation that remains in power except for a 5-year lapse in 2016 - 2021.

Since the democratic transition began in 2011, there has been continuous violence as 280 people have been killed and 140,000 forced to flee from their homes in the Rakhine state in 2014.

[255] A UN envoy reported in March 2013 that unrest had re-emerged between Myanmar's

Buddhist and

Muslim communities, with violence spreading to towns that are located closer to Yangon.

[256]

Government reforms

According to the

Crisis Group,

[257] since Myanmar transitioned to a new government in August 2011, the country's human rights record has been improving. Previously giving Myanmar its lowest rating of 7, the 2012

Freedom in the World report also notes improvement, giving Myanmar a 6 for improvements in civil liberties and political rights, the release of political prisoners, and a loosening of restrictions.

[258] In 2013, Myanmar improved yet again, receiving a score of 5 in civil liberties and 6 in political freedoms.

[259]

The government has assembled a

National Human Rights Commission that consists of 15 members from various backgrounds.

[260] Several activists in exile, including Thee Lay Thee Anyeint members, have returned to Myanmar after President Thein Sein's invitation to expatriates to return home to work for national development.

[261] In an address to the United Nations Security Council on 22 September 2011, Myanmar's Foreign Minister

Wunna Maung Lwin confirmed the government's intention to release prisoners in the near future.

[262]

The government has also relaxed reporting laws, but these remain highly restrictive.

[263] In September 2011, several banned websites, including YouTube,

Democratic Voice of Burma and

Voice of America, were unblocked.

[264] A 2011 report by the

Hauser Center for Nonprofit Organizations found that, while contact with the Myanmar government was constrained by donor restrictions, international humanitarian non-governmental organisations (NGOs) see opportunities for effective advocacy with government officials, especially at the local level. At the same time, international NGOs are mindful of the ethical quandary of how to work with the government without bolstering or appeasing it.

[265]

A Rohingya refugee camp in Bangladesh

Following Thein Sein's first ever visit to the UK and a meeting with Prime Minister

David Cameron, the Myanmar president declared that all of his nation's political prisoners will be released by the end of 2013, in addition to a statement of support for the well-being of the Rohingya Muslim community. In a speech at

Chatham House, he revealed that "We [Myanmar government] are reviewing all cases. I guarantee to you that by the end of this year, there will be no prisoners of conscience in Myanmar.", in addition to expressing a desire to strengthen links between the UK and Myanmar's military forces.

[266]

Homosexual acts are

illegal in Myanmar and can be punishable by life imprisonment.

[267][268]

In 2016, Myanmar leader

Aung San Suu Kyi was accused of failing to protect Myanmar's

Muslim minority.

[269] Since August 2017

Doctors Without Borders have treated 113 Rohingya refugee females for sexual assault with all but one describing military assailants.

[270]

Economy

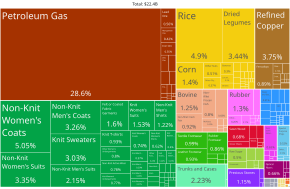

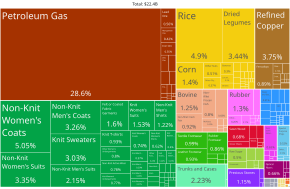

A proportional representation of Myanmar exports, 2019

Main article:

Economy of Myanmar

Further information:

Golden Triangle (Southeast Asia),

Transport in Myanmar, and

Oil and gas industry in Myanmar

Myanmar's

economy is one of the

fastest growing economies in the world with a nominal GDP of US$76.09 billion in 2019 and an estimated purchasing power adjusted GDP of US$327.629 billion in 2017 according to the World Bank.

[271][

improper synthesis?] Foreigners are able to legally lease but not own property.

[272] In December 2014, Myanmar set up its first stock exchange, the

Yangon Stock Exchange.

[273]

The informal economy's share in Myanmar is one of the biggest in the world and is closely linked to corruption, smuggling and illegal trade activities.

[274][275] In addition, decades of civil war and unrest have contributed to Myanmar's current levels of poverty and lack of economic progress. Myanmar lacks adequate

infrastructure. Goods travel primarily across the Thai border (where most illegal drugs are exported) and along the Irrawaddy River.

[276]

Both China and India have attempted to strengthen ties with the government for economic benefit in the early 2010s. Many Western nations, including the United States and Canada, and the

European Union, historically imposed investment and trade sanctions on Myanmar. The United States and European Union eased most of their sanctions in 2012.

[277] From May 2012 to February 2013, the United States began to lift its economic sanctions on Myanmar "in response to the historic reforms that have been taking place in that country."

[278] Foreign investment comes primarily from China, Singapore, the Philippines, South Korea, India, and Thailand.

[279] The military has stakes in some major industrial corporations of the country (from oil production and consumer goods to transportation and tourism).

[280][281]

Economic history

The trains are relatively slow in Myanmar. The railway trip from

Bagan to

Mandalay takes about 7.5 hours (179 km).

Under the

British administration, the people of Burma were at the bottom of the social hierarchy, with

Europeans at the top, Indians, Chinese, and Christianized minorities in the middle, and Buddhist Burmese at the bottom.

[282] Forcefully integrated into the world economy, Burma's economy grew by involving itself with extractive industries and

cash crop agriculture. However, much of the wealth was concentrated in the hands of Europeans. The country became the world's largest exporter of

rice, mainly to European markets, while other colonies like India suffered mass starvation.

[283] Being a follower of free market principles, the British opened up the country to large-scale immigration with Rangoon exceeding New York City as the greatest immigration port in the world in the 1920s. Historian

Thant Myint-U states, "This was out of a total population of only 13 million; it was equivalent to the United Kingdom today taking 2 million people a year." By then, in most of Burma's largest cities,

Rangoon,

Akyab,

Bassein and

Moulmein, the Indian immigrants formed a majority of the population. The Burmese under British rule felt helpless, and reacted with a "racism that combined feelings of superiority and fear".

[282]

Crude oil production, an indigenous industry of

Yenangyaung, was taken over by the British and put under

Burmah Oil monopoly. British Burma began exporting crude oil in 1853.

[284] European firms produced 75% of the world's teak.

[28] The wealth was however, mainly concentrated in the hands of Europeans. In the 1930s, agricultural production fell dramatically as international rice prices declined and did not recover for several decades.

[285] During the Japanese invasion of Burma in World War II, the British followed a

scorched earth policy. They destroyed major government buildings, oil wells and mines that developed for tungsten (

Mawchi), tin, lead and silver to keep them from the Japanese. Myanmar was bombed extensively by the Allies.[

citation needed]

After independence, the country was in ruins with its major infrastructure completely destroyed. With the loss of India, Burma lost relevance and obtained independence from the British. After a parliamentary government was formed in 1948, Prime Minister

U Nu embarked upon a policy of nationalisation and the state was declared the owner of all of the land in Burma. The government tried to implement an eight-year plan partly financed by injecting money into the economy, but this caused inflation to rise.

[286] The

1962 coup d'état was followed by an economic scheme called the

Burmese Way to Socialism, a plan to nationalise all industries, with the exception of

agriculture. While the economy continued to grow at a slower rate, the country eschewed a Western-oriented development model, and by the 1980s, was left behind capitalist powerhouses like

Singapore which were integrated with Western economies.

[287][84] Myanmar asked for admittance to a

least developed country status in 1987 to receive debt relief.

[288]

Agriculture

Rice is Myanmar's largest agricultural product.

Further information:

Agriculture in Myanmar

The major agricultural product is

rice, which covers about 60% of the country's total cultivated land area. Rice accounts for 97% of total food grain production by weight. Through collaboration with the

International Rice Research Institute 52 modern rice varieties were released in the country between 1966 and 1997, helping increase national rice production to 14 million tons in 1987 and to 19 million tons in 1996. By 1988, modern varieties were planted on half of the country's ricelands, including 98 per cent of the irrigated areas.

[289] In 2008 rice production was estimated at 50 million tons.

[290]

Extractive industries

Myanmar produces precious stones such as

rubies,

sapphires,

pearls, and

jade.

Rubies are the biggest earner; 90% of the world's rubies come from the country, whose red stones are prized for their purity and hue. Thailand buys the majority of the country's gems. Myanmar's "Valley of Rubies", the mountainous

Mogok area, 200 km (120 mi) north of

Mandalay, is noted for its rare pigeon's blood rubies and blue sapphires.

[291]

Many

U.S. and

European jewellery companies, including Bulgari, Tiffany and Cartier, refuse to import these stones based on reports of deplorable working conditions in the mines.

Human Rights Watch has encouraged a complete ban on the purchase of Burmese gems based on these reports and because nearly all profits go to the ruling junta, as the majority of mining activity in the country is government-run.

[292] The government of Myanmar controls the gem trade by direct ownership or by joint ventures with private owners of mines.

[293]

Rare-earth elements are also a significant export, as Myanmar supplies around 10% of the world's rare earths.

[294] Conflict in Kachin State has threatened the operations of its mines as of February 2021.

[295][296]

Other industries include agricultural goods, textiles, wood products, construction materials, gems, metals, oil and natural gas.

Myanmar Engineering Society has identified at least 39 locations capable of geothermal power production and some of these hydrothermal reservoirs lie quite close to Yangon which is a significant underutilised resource for electrical production.

[297]

Tourism

Main article:

Tourism in Myanmar

Tourists in Myanmar

U Bein Bridge

U Bein Bridge in Mandalay.

The government receives a significant percentage of the income of private-sector tourism services.

[298] The most popular available tourist destinations in Myanmar include big cities such as

Yangon and

Mandalay; religious sites in

Mon State,

Pindaya,

Bago and

Hpa-An; nature trails in

Inle Lake,

Kengtung,

Putao,

Pyin Oo Lwin; ancient cities such as

Bagan and

Mrauk-U; as well as beaches in

Nabule,

[299] Ngapali,

Ngwe-Saung,

Mergui.

[300] Nevertheless, much of the country is off-limits to tourists, and interactions between foreigners and the people of Myanmar, particularly in the border regions, are subject to police scrutiny. They are not to discuss politics with foreigners, under penalty of imprisonment and, in 2001, the Myanmar Tourism Promotion Board issued an order for local officials to protect tourists and limit "unnecessary contact" between foreigners and ordinary Burmese people.

[301]

The most common way for travellers to enter the country is by air.

[302] According to the website

Lonely Planet, getting into Myanmar is problematic: "No bus or train service connects Myanmar with another country, nor can you travel by car or motorcycle across the border – you must walk across." They further state that "It is not possible for foreigners to go to/from Myanmar by sea or river."

[302] There are a few border crossings that allow the passage of private vehicles, such as the border between

Ruili (China) to

Mu-se, the border between

Htee Kee (Myanmar) and

Phu Nam Ron (Thailand)—the most direct border between

Dawei and

Kanchanaburi, and the border between

Myawaddy and

Mae Sot, Thailand. At least one tourist company has successfully run commercial overland routes through these borders since 2013.

[303]

Flights are available from most countries, though direct flights are limited to mainly Thai and other

ASEAN airlines. According to

Eleven magazine, "In the past, there were only 15 international airlines and increasing numbers of airlines have begun launching direct flights from Japan, Qatar, Taiwan, South Korea, Germany and Singapore."

[304] Expansions were expected in September 2013 but are mainly

Thai and other Asian-based airlines.

[304]

Demographics

Main article:

Demographics of Myanmar

A block of apartments in downtown Yangon, facing

Bogyoke Market. Much of Yangon's urban population resides in densely populated flats.

| Year | Million |

|---|

| Population[305][306] | |

|---|

| 1950 | 17.1 |

| 2000 | 46.1 |

| 2021 | 53.8 |

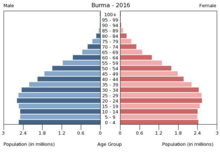

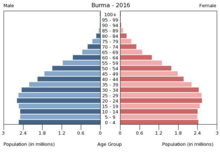

Population pyramid 2016

The provisional results of the

2014 Myanmar Census show that the total population is 51,419,420.

[307] This figure includes an estimated 1,206,353 persons in parts of northern

Rakhine State,

Kachin State and

Kayin State who were not counted.

[308] People who were out of the country at the time of the census are not included in these figures. There are over 600,000 registered

migrant workers from Myanmar in

Thailand, and millions more work illegally. Burmese citizens account for 80% of all migrant workers in Thailand.

[309] The national population density is 76 per square kilometre (200/sq mi), among the lowest in Southeast Asia.

Myanmar's fertility rate as of 2011 is 2.23, which is slightly above

replacement level[310] and is low compared to

Southeast Asian countries of similar economic standing, such as

Cambodia (3.18) and Laos (4.41).

[310] There has been a significant decline in fertility in the 2000s, from a rate of 4.7 children per woman in 1983, down to 2.4 in 2001, despite the absence of any national population policy.

[310][311][312] The fertility rate is much lower in urban areas.

The relatively rapid decline in fertility is attributed to several factors, including extreme delays in marriage (almost unparalleled among developing countries in the region), the prevalence of illegal abortions, and the high proportion of single, unmarried women of reproductive age, with 25.9% of women aged 30–34 and 33.1% of men and women aged 25–34 being single.

[312][313]

These patterns stem from economic dynamics, including high income inequality, which results in residents of reproductive age opting for delay of marriage and family-building in favour of attempting to find employment and establish some form of wealth;

[312] the average age of marriage in Myanmar is 27.5 for men, 26.4 for women.

[312][313]

listen), /ˈmjɑːnmɑːr/. Dictionaries and other sources also report pronunciations with three syllables /ˈmiːənmɑːr/, /miˈænmɑːr/, /ˌmaɪənˈmɑːr/, /maɪˈɑːnmɑːr/, /ˈmaɪænmɑːr/.[48]

listen), /ˈmjɑːnmɑːr/. Dictionaries and other sources also report pronunciations with three syllables /ˈmiːənmɑːr/, /miˈænmɑːr/, /ˌmaɪənˈmɑːr/, /maɪˈɑːnmɑːr/, /ˈmaɪænmɑːr/.[48]